Writing in Africa Today (vol. 50, no. 3, 2004), Professor Joe Oloka-Onyango describes Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, as ‘a conundrum of paradoxes'. The latest spat between Uganda and Kenya over the little island of Migingo in Lake Victoria illustrates the never-ending bag of paradoxes that is Museveni.

For a start, the idea of an East African Community was largely mooted by the initiative of Museveni. Using the less threatening mediation of Benjamin Mkapa, then president of the United Republic of Tanzania, Museveni managed to get a suspicious and more astute Daniel arap Moi to commit and support this idea. The idea has grown and initiatives to fast-track integration are at an advanced stage. But just when the idea appeared to be coming to fruition, Museveni unleashed the Migingo controversy. If left unchecked, this controversy is set to roll back or undo the drive to regional integration in East Africa.

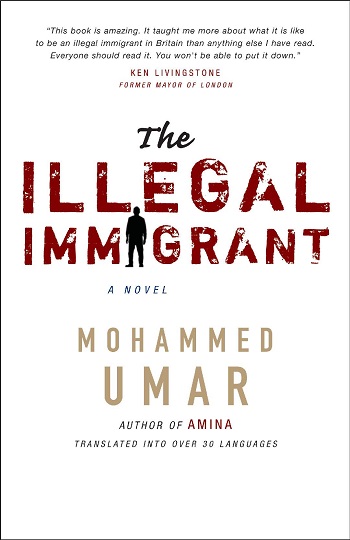

http://www.pambazuka.org/images/articles/432/where_is_uhuru_murunga.gif

There is no doubt that for reasons that reside in the weird leadership character of Kenyan President Mwai Kibaki, the legal, diplomatic and political means have already been given a chance to unfold. Not only has President Kibaki been strangely quiet about an issue of such national importance, but his ministers and negotiators have stood calm as Ugandan forces have occupied and hoisted the Ugandan flag on the island, harassed innocent citizens and adopted a bellicose posture every time Ugandan officials have trooped around the island. Kenyans on the island have not complained about Ugandan citizens, but they consistently complain about the Ugandan armed forces.

What threatens to undo all the goodwill that might heal this controversy is Museveni’s love for the military option coupled with his strong belief in ‘individual destiny’. The notion of ‘individual destiny’ does not frontally convey the political danger that Museveni’s political biography poses to the vision of regional integration. This is a political biography that is strongly narcissistic. Writing on this in ChemChemi: International Journal of Arts and Social Sciences of Kenyatta University (vol. 1, December 1999), the respected Kenyan historian Bethwell Ogot described Museveni as a ‘Ugandan Narkissos’ and aptly captured the variety of dangers rolled into this one character.

The word narcissism derives from the name of a Greek youth Narkissos, who fell in love with his own reflection in water. If we understand narcissism to mean ‘a tendency to self-worship, an absorption in one’s own personal perfection’ and we agree with Oloka-Onyango that Museveni shares with Idi Amin and Muammar Gaddafi 'an affection for matters military' and 'an unflagging belief in the efficacy of military action to solve virtually every political problem', then Kenyans have a right to be circumspect of every one of Museveni’s promises for an amicable solution to the Migingo issue. This view is justified. Since the Migingo controversy came to light, Museveni had promised to allow a proper survey to be undertaken so as to provide a scientific basis of resolving the controversy. The Kenyan team on this issue has been uncharacteristically calm even in the face of repeated provocation from Uganda and amateurish prodding in Kenya for a more robust response. But on Tuesday 12 May 2009, Museveni’s characteristic ‘fit of pique’ overwhelmed him. This happened only one day after the survey aimed at resolving the issue was launched.

Speaking to the BBC after a lecture at the University of Dar es Salaam, Museveni slammed the Wajalous (the Luos). 'The island is in Kenya, the water is in Uganda,' he argued:

'But the Wajaluos are mad, they want to fish here but this is Uganda … hii nchi uhuru [this is a sovereign country]. It is written here in English … from this point, the border will continue to go in a straight line to the most northern point of Suba Island. Mpaka inazunguka kisiwa [the border surrounds the island] … one foot into the water and you’re in Uganda.'

In response, Kenyans have gone ballistic and their MPs have declared Uganda an unfriendly country. In contrast, Ugandans know Museveni better and much of his verbiage has gone almost unnoticed. I inquired from a colleague in Kampala who closely follows regional politics what he thought about Museveni’s outburst. 'Outburst on what?', came the response, before he added that 'He [Museveni] is always bursting.'

Ugandans are only too aware of the military basis on which Museveni has built his profile, with serious negative consequences within. This has undermined opposition politics in the country as Museveni has assaulted political freedom and guaranteed an ‘absence of enduring peace’. In 2003, one Ugandan professor described him as the ‘revolutionary of the World Bank'. With this the professor captured the irony of ‘a market-reformed Marxist’.

An essentially 'militaristic and opportunistic vision of the process of integration' has blossomed under Museveni. He has loomed large in most conflicts in the region in Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sudan. Kenya was among the first testing-ground for his military driven idea of regional integration in 1987. When it became clear that Moi would not be an easy adversary – especially after he firmly repulsed NRA soldiers at the Busia border and closed the border (thereby asphyxiating landlocked Uganda) – Museveni retreated. Henceforth, he went on an empty tirade seeking to find a solution out of Uganda’s landlocked trap. As far as I can tell, he has not yet solved this problem.

It is obvious that Museveni finds Kibaki an easier adversary and the Kenyan grand coalition mix-up as an opportunity. Prone to a hands-off style in which critical national crises spiral out of control before he acts, Kibaki’s style might be the reason why the Migingo controversy might escalate. Indeed, there is a sense that Museveni is acutely aware of the internal workings of Kenyan politics, workings which do not predispose Kibaki to act quickly and firmly on the Migingo issue.

In other words, both Kibaki and Museveni have a common nemesis in Kenya’s prime minister, Raila Odinga. They are deeply suspicious of him, Museveni for reasons that might relate to his regional aspirations and Kibaki largely for local political manoeuvring. One only needs to note Museveni’s shamefully rude reference to the Wajaluos which he intended as a denigrating and dismissive reference. For him, the issue is not about Kenya, it is about 'those Jaluos who were rioting... wanang’oa [uprooting] railway'. But Museveni is appropriating a language common in Kenya. The Luo are supposed to be riotous and unreasonable and do not enjoy any affinity with other Kenyans. This was and continues to be a common reference in sections of Kenya. In 2007, as in earlier electoral contests where a Luo candidate vied for the presidency, this reference was used to suggest that a Luo could never be elected as Kenya’s president. The more President Kibaki procrastinates on Migingo, the more obvious it becomes that he treats this as a problem of those 'riotous' Jaluos.

Those who understand Museveni, like Joe Oloka-Onyango or Andrew Mwenda, will acknowledge his display of ‘abusive and dismissive language’ in public. This is often accompanied by a tendency to disparage those who disagree with him. Keen observers would have noticed such rudeness towards Raila Odinga during the swearing-in of the cabinet in 2008. In the middle of a sentence, he cynically asked 'which is that Raila’s party?' Many people think that Museveni aspires to become the first head of an integrated East African Community. If this were the case, East Africans should be made aware of Museveni’s troubling ‘disdain for, and fear of, opposition politics'. In Kenya, in contrast, opposition politics has been the bedrock of an incipient movement to reform.

Kenyan politics shares one thing with Tanzanian politics. Both are anchored in civilian rule while Uganda’s is militaristic. Recently, Museveni upped the ante by going for militarised family rule. For a family that has 'no accomplishments of their own', Ugandan journalist Andrew Mwenda concludes, their ‘success’ rests in living off Museveni’s patronage. Thus, Janet Museveni is minister for Karamoja region, first lady, and MP for Ruhaama constituency, while his son Muhoozi Kainerugaba was last year elevated to the position of special force commander, the president's younger brother Salim Saleh (Caleb Akandwanaho) is a senior presidential advisor on defence and his daughter, Natasha Karugire, is a private secretary to the president. Even if one wished to give Museveni a chance in East Africa, militarised family rule must surely be outdated.

Does one need to wonder when Museveni’s love for the people dissipated? In December 1987, following protracted tension between Kenya and Uganda, Museveni held a press conference at which he accused Moi of 'trying to force me to fight Kenyans'. Equating this to 'trying to force me to fight my children, or my brothers, or my sisters', he concluded that the 'Uganda government knows that there is no cause for conflict between the people of Kenya and the people of Uganda.' 'I am talking about the people', he elaborated, 'They are not conflicting over land, they are not conflicting over water, so why should we conflict with the Kenyan people?'

Today, Museveni’s short memory and his over-extended military ego reflect an individual who cares less about the people of Kenya or Uganda. Indeed, one wonders if the Kenyan leadership cares for the people of Uganda or Kenya, but this must be the critical question as we strive for a quick and amicable end to the Migingo controversy.

* Godwin Murunga is the editor of .

* Please send comments to [email protected] or comment online at http://www.pambazuka.org/.

- Log in to post comments

- 577 reads

cc In the wake of Kenya and Uganda's confrontation over the small island of Migingo in Lake Victoria, Godwin Murunga argues that the actions of Uganda's President Yoweri Museveni are very much in keeping with an essentially paradoxical nature. While in broad agreement with

cc In the wake of Kenya and Uganda's confrontation over the small island of Migingo in Lake Victoria, Godwin Murunga argues that the actions of Uganda's President Yoweri Museveni are very much in keeping with an essentially paradoxical nature. While in broad agreement with