Cuba and Southern African Liberation

One of the greatest military victories in African history, conducted jointly by Angolan and Cuban troops in 1987-1988 in the Angolan town of Cuito Cuanavale, is little known in global history

Cuba's direct, extensive, critical and decisive role in the struggle against the apartheid regime in South Africa is little known in the West. As 2012 marches into 2013, we are in the midst of the 25th anniversary of a series of military engagements that profoundly altered the history of southern Africa. In 1987-1988, a decisive series of battles occurred around the southeastern Angolan town of Cuito Cuanavale. When it occurred, these battles were the largest military engagements in Africa since the North African battles of the Second World War. Arrayed on one side were the armed forces of Cuba, Angola and the South West African People's Organization (SWAPO), on the other, the South African Defense Forces, military units of the Union for the Total National Independence of Angola (UNITA - the South African proxy organization) and the South African Territorial Forces of Namibia (then still illegally occupied by Pretoria).

Cuito Cuanavale is marginalized in the west, frequently ignored, almost as if it had never occurred. However, the overarching significance of the battle cannot be erased. It was a critical turning point in the struggle against apartheid. From November 1987 to March 1988, the South African armed forces repeatedly tried and failed to capture Cuito Cuanavale. In southern Africa, the battle has attained legendary status. It is considered THE debacle of apartheid: a defeat of the South African armed forces that altered the balance of power in the region and heralded the demise of racist rule in South Africa.

Cuito Cuanavale decisively thwarted Pretoria's objective of establishing regional hegemony (a strategy which was vital to defending and preserving apartheid), directly led to the independence of Namibia and accelerated the dismantling of apartheid. The battle is often referred to as the African Stalingrad of apartheid. Cuba's contribution was crucial as it provided the essential reinforcements, material and planning.

CUITO CUANAVALE: AFRICAN STALINGRAD

In July 1987, the FAPLA, the Angolan armed forces, launched an offensive against UNITA, the apartheid state's surrogate. The Cubans objected to this military operation because it would create the opportunity for a South African invasion, which is what transpired. The South Africans invaded, stopped and threw back the Angolan forces. After terrible human and material losses, the Angolans were forced into a headlong retreat to the town and strategic military base of Cuito Cuanavale.

As the fighting became centred on Cuito Cuanavale, the Angolan Armed forces were placed in an extremely precarious situation, with its most elite formations facing annihilation. Indeed, Angola faced an existential threat. If Cuito Cuanavale fell to South Africa then the rest of the country would be at the mercy of the invaders. Angolan General Antonio dos Santos underscored the overarching significance of the town's defence stating that if they [the South Africans"> won at Cuito Cuanavale, the road would be open to the north of Angola.’

Determined to transform its initial military success into a fatal blow against an independent Angola, Pretoria committed its best troops and most sophisticated military hardware to the capture of Cuito Cuanavale. As the situation of the besieged Angolan troops became critical, Havana was asked by the Angolan government to intervene. On 15 November 1987 Cuba decided to reinforce its forces by sending fresh detachments, arms and equipment, including tanks, artillery, anti-aircraft weapons and aircraft. Eventually Cuban troop strength would rise to more than 50, 000. It must be emphasized that for a small country such as Cuba the deployment of 50,000 troops would be the equivalent of the U.S. deploying more than a million soldiers, or Canada more than one hundred thousand.

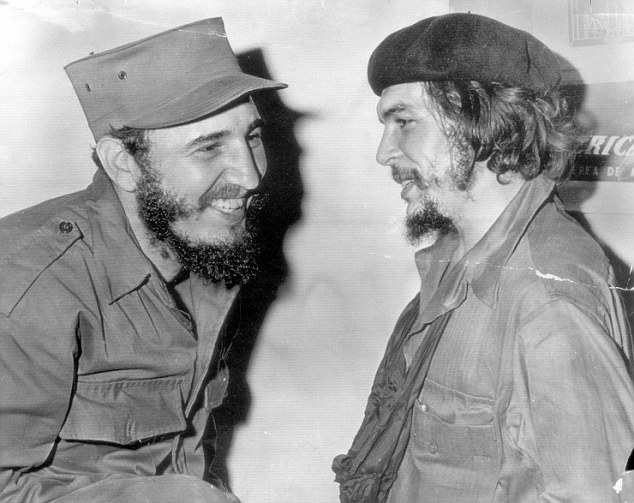

CUBA’S VITAL ROLE

The Cuban commitment was immense. Fidel Castro stated that the Cuban Revolution had ‘put its own existence at stake, it risked a huge battle against one of the strongest powers located in the area of the Third World, against one of the richest powers, with significant industrial and technological development, armed to the teeth, at such a great distance from our small country and with our own resources, our own arms. We even ran the risk of weakening our defenses, and we did so. We used our ships and ours alone, and we used our equipment to change the relationship of forces, which made success possible in that battle. We put everything at stake in that action...’

The Cuban government viewed preventing the fall of Cuito Cuanavale as imperative. A South African victory would have meant not only the capture of the town and the destruction of the best Angolan military formations, but, quite possibly, the end of Angola's existence as an independent country. The Cuban revolutionary leadership also decided to go further than the defence of Cuito Cuanavale. They decided to deploy the necessary forces and employ a plan that would both put an end once and for all to South African aggression against Angola and deliver a decisive blow against the racist state. The successful defence of Cuito Cuanavale would be the prelude to a grand and far reaching strategy that would transform the balance of power in the region.

South Africa's efforts to seize Cuito Cuanavale were stymied by the Cubans and Angolans. With the South Africans preoccupied at Cuito Cuanavale, the Cubans achieved a strategic coup by carrying-out an outflanking maneuver. To the west of Cuito Cuanavale and along the Angolan/Namibian border, Havana deployed 40,000 Cuban troops, supported by 30,000 Angolan and 3,000 SWAPO troops. Pretoria had become so focused on seizing Cuito Cuanavale that they had left themselves exposed to a major military counterstroke.

The Cubans, together with Angolan and SWAPO forces advanced toward Namibia. This advance exposed the insecurity and vulnerability of the South African troops in northern Namibia. Such was this vulnerability that a senior South African officer said, ‘Had the Cubans attacked [Namibia"> they would have over-run the place. We could not have stopped them.’ This was further compounded by South African debacles at the end of June 1988 at Caluque and Tchipia, where the South Africans suffered serious defeats, which were described by a South African newspaper as ‘a crushing humiliation.’ Cuba also achieved air supremacy. Facing the new powerful force assembled in southern Angola and having lost control of the skies, the South Africans withdrew from Angola.

This defeat on the ground forced South Africa to the negotiating table, resulting in Namibian independence and dramatically hastening the end of apartheid. The regional balance of power had been fundamentally transformed. The respected scholar Victoria Brittan observed that Cuito Cuanavale became ‘a symbol across the continent that apartheid and its army were no longer invincible.’ In a July 1991 speech delivered in Havana, Nelson Mandela underscored Cuito Cuanavale's and Cuba's vital role:

‘The Cuban people hold a special place in the hearts of the people of Africa. The Cuban internationalists have made a contribution to African independence, freedom and justice unparalleled for its principled and selfless character. We in Africa are used to being victims of countries wanting to carve up our territory or subvert our sovereignty. It is unparalleled in African history to have another people rise to the defense of one of us. The defeat of the apartheid army was an inspiration to the struggling people in South Africa!

Without the defeat of Cuito Cuanavale our organizations would not have been unbanned! The defeat of the racist army at Cuito Cuanavale has made it possible for me to be here today! Cuito Cuanavale was a milestone in the history of the struggle for southern African liberation!’

In 1994, Mandela further declared: ‘If today all South Africans enjoy the rights of democracy; if they are able at last to address the grinding poverty of a system that denied them even the most basic amenities of life, it is also because of Cuba's selfless support for the struggle to free all of South Africa's people and the countries of our region from the inhumane and destructive system of apartheid. For that, we thank the Cuban people from the bottom of our heart.’

SOUTH AFRICA'S WAR OF TERROR

The 1987-88 military reversal in Angola constituted a mortal blow to the apartheid regime. The battle of Cuito Cuanavale ended its dream (nightmare for the region’s peoples) of establishing hegemony in southern Africa as a means by which to extend the life of the racist regime. Toward this end, Pretoria had militarized the South Africa state, fashioning it into the sword to defend the racist system and wage a regional war of terror.

From 1975 to 1988, the South Africa armed forces embarked on a campaign of massive destabilization of the region. The war of destabilization wrought a terrible toll. The financial and human cost can not only be measured in direct damage and deaths but also in the premature deaths and projected economic loss caused by destruction of infrastructure, agriculture and power networks. While, it is very difficult to estimate the economic cost and damage, it was undoubtedly enormous. One study calculates that up to 1988, the total economic cost for the Frontline States was calculated to be in excess of $US 45 billion: for example, Angola: $US 22 billion; Mozambique: $US 12 billion; Zambia: $US 7 billion; Zimbabwe: $US 3 billion.

The loss of life was immense. The South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission underscored that ‘the number of people killed inside the borders of the country in the course of the liberation struggle was considerably lower than those who died outside...the majority of the victims of the South African's government attempts to maintain itself in power were outside South Africa. Tens of thousands of people died as a direct or indirect result of the South African's government aggressive intent towards its neighbours. The lives and livelihoods of hundreds of thousands others were disrupted by the systematic targeting of infrastructure in some of the poorest nations in Africa.’

Between 1981 and 1988, an estimated 1.5 million people were (directly or indirectly) killed, including 825, 000 children. This was the result of Pretoria sponsored insurgencies (namely, UNITA in Angola and Renamo in Mozambique) and direct military actions by the South African armed forces. South Africa launched numerous bombing raids, armed incursions and assassinations against surrounding countries. One notorious example was the 4 May 1978 massacre in a camp for Namibian refugees, located in the town of Kassinga, southwestern Angola, where a South African air and paratrooper attack killed hundreds of people and, also, took hundreds of prisoners.

Perhaps, the late Julius Nyerere, summed up the situation best when in 1986, as President of Tanzania, he observed:

‘When is war not war? Apparently when it is waged by the stronger against the weaker as a pre-emptive strike.' When is terrorism not terrorism? Apparently when it is committed by a more powerful government against those at home and abroad who are weaker than itself and whom it regards as a potential threat or even as insufficiently supportive of its own objectives. Those are the only conclusions one can draw in the light of the current widespread condemnation of aggression and terrorism, side by side with the ability of certain nations to attack others with impunity, and to organize murder, kidnapping and massive destruction with the support of some permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. South Africa is such a country.’

AFRICA’S CHILDREN RETURN

The Cuban Revolution's involvement with Angola began in the 1960s when relations were established with the Movement for the Popular Liberation of Angola (MPLA). The MPLA was the principal organization in the struggle to liberate Angola from Portuguese colonialism. In 1975, the Portuguese withdrew from Angola. However, in order to stop the MPLA from coming to power, the U.S. government had already been funding various groups, in particular the Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) led by the notorious Jonas Savimbi.

In August 1975, South Africa, with the support of Washington, invaded Angola. This was followed by a much larger invasion in October. On 5 November 1975 in response to a request from the Angolan government, the Cuban government deployed combat troops in Operation Carlota, named after the leader of a revolt against slavery that took place in Cuba on 5 November 1843.

Cuban military assistance was decisive in not only stopping the South African drive to Luanda, the capital but also pushing the South Africans out of Angola. The defeat of the South African forces was a major development in the African anti-colonial struggle. The World, a Black South African newspaper, underscored the significance: ‘Black Africa is riding the crest of a wave generated by the Cuban success in Angola. Black Africa is tasting the heady wine of the possibility of realizing the dream of "total liberation.’

Cuban involvement in Southern Africa has been repeatedly dismissed as surrogate activity for the Soviet Union. This insidious myth has been unequivocally refuted. John Stockwell, the director of CIA operations in Angola during and in the immediate aftermath of the 1975 South African invasion, in his memoir, ‘In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story’, stated ‘we learned that Cuba had not been ordered into action by the Soviet Union. To the contrary, the Cuban leaders felt compelled to intervene for their own ideological reasons.’ In his acclaimed book, ‘Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington and Africa, 1959-76’, Piero Gliejeses demonstrated that the Cuban government - as it had repeatedly asserted - decided to dispatch combat troops to Angola only after the Angolan government had requested Cuba's military assistance to repel the South Africans, refuting Washington's assertion that South African forces intervened in Angola only after the arrival of the Cuban forces and the Soviet Union had no role in Cuba's decision and were not even informed prior to deployment. In short, Cuba was not the puppet of the USSR. Even ‘The Economist’ magazine (no friend of Cuba) in a 2002 article, acknowledged that the Cuban government acted on its ‘own initiative.’

Cuba is often described as the only foreign country to have gone to Africa and gone away with nothing but the coffins of its sons and daughters who died in the struggles to liberate Africa. More than 330,000 Cubans served in Angola. More than 2, 000 Cubans died in defence of Angolan independence and right of self-determination. In paying tribute to Cuba's assistance to African liberation struggles, Amilcar Cabral the celebrated leader of the anti-colonial and national liberation struggle in Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde, stated: ‘I don't believe in life after death, but if there is, we can be sure that the souls of our forefathers who were taken away to America to be slaves are rejoicing today to see their children reunited and working together to help us be independent and free.’

Cuba's example is a profound challenge to those who believe and argue that only real politick, national self-interest and the pursuit of power and wealth are - and can be - the only guides, determinants and sources of foreign policy.

Cuba's role in Angola illustrates the division between those who fight for the cause of freedom, liberation and justice, to repel invaders and colonialists, and those who fight against just causes, those who wage war to occupy, colonize and oppress.

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org or comment online at Pambazuka News.

* Isaac Saney teaches history at Dalhousie University and Saint Mary's University, Halifax, Canada, He is co-chair and National Spokesperson, Canadian Network On Cuba. He is currently putting the final touches on the book manuscript, ‘From Soweto to Cuito Cuanavale: Cuba, the End of Angola and the End of Apartheid’.