The political and economic challenges facing provision of municipal infrastructure in Durban

Started 10 years ago, South Africa’s shack dwellers movement Abahlali baseMjondolo has mounted a remarkable struggle – often at a terrible cost - to protect and promote the rights of impoverished people in the towns. This inspirational story shows what poor people can achieve when they organize themselves outside the state, political parties and NGOs.

[This was a presentation delivered at Wits and University of Michigan Workshop on the Politics of Municipal Infrastructure held at the Durban University of Technology, 12 July 2016.]

I wish to take this opportunity to thank the organisers of this workshop for recognising the struggle of Abahlali baseMjondolo. Today I wish to extend my gratitude to Wits and to Michigan for inviting me to share Abahlali’s experience in our dignified struggle which includes struggle for land, housing, water, sewerage, electricity and transport.

But before I share our experience, may I take this opportunity to briefly introduce to you Abahlali baseMjondolo Movement SA. The movement was formed in the Kennedy Road shack settlement in Clare Estate here in Durban in 2005. It was formed to fight for, protect, promote and advance the interests and dignity of shack dwellers and other impoverished people in South Africa.

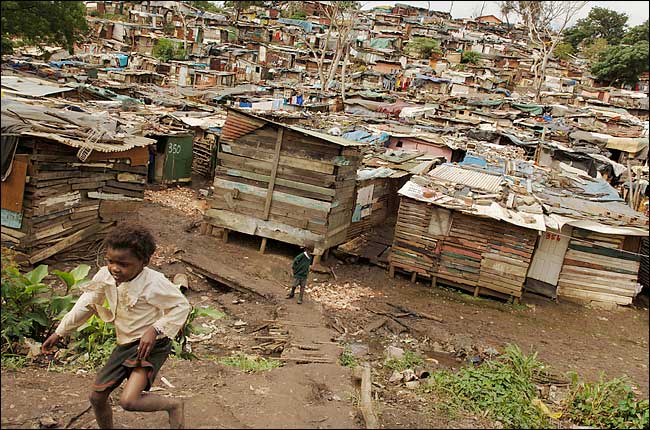

Kennedy Road settlement is one of many shack settlements in Durban that are established in a well located area. It is located in a middle class suburb with economic opportunities, good schools and other infrastructures at its disposal. One of these infrastructures is that it is close to the city’s biggest dump run by Durban Solid Waste. Some people sourced building materials from the dump and some made their livelihood here. But many others worked as domestic workers, security guards, construction workers, informal traders and so on.

At the time of the movement’s formation Kennedy Road was facing eviction. We were told that the dump itself was very health hazardous for residents within the shack settlement. We were told that there was a migrating methane gas underneath the soil to the settlement which was even more dangerous for residents. Other settlements in the middle class suburbs were also facing eviction. Always people would be told that the eviction was needed as a result of unsafe conditions. People might be told that the land was too steep or unstable to build housing for impoverished people although middle class people were living well on the same land. In Kennedy Road the middle class residents just across the road were told that there was no risk to them from the dump.

The conditions were very bad in the settlement due to the lack of infrastructure. There was no refuse collection and so rubbish quickly accumulated. We were threatened with big rats that from time to time were seen running across the settlement. A year later a six-month baby was killed by a rat while sleeping with her mom. We were also told that the land was too steep and unstable for housing development.

Because there was no electricity and very few taps fires were a constant risk. There were only five water stand pipes that served around 6,000 people. This meant that it was very difficult to fight fires. In 2006 a one-year-old child, Mhlengi Khumalo, was killed in a shack fire and as time passed several more people were burnt to death. In most cases the fire department would take up to 30 minutes to arrive in the settlement and sometimes they did not have sufficient water. If they did have sufficient water they often could not reach burning shacks because there were no access roads. Abahlali discovered that eThekwini municipality had a policy not to electrify shack settlements. So, we had a situation where there was not enough water stand pipes, inadequate access roads, no fire break and electricity provision was prohibited

The shortage of taps also meant that people spent a lot of time queuing to fetch water. Carrying water down steep hills was dangerous when it rained and the paths were muddy. This made everyday life very difficult. In some families women carried most of this burden. The shortage of water was very difficult for people who were sick, especially when they had diarrhoea.

The lack of electricity also meant that people had to use candles for light, gas stoves to cook and fire to keep warm all of which raise the risk of fire. Learners and students had to study by candle-light.

There were 43 ventilated pit latrines that had been blocked for years. People were deeply shocked when children were found eating the worms that emanated from these toilets thinking that they were rice. There were 6 portable toilets. With more than a thousand people for each of these portable toilets they were in a terrible condition and always blocked. Women were at particular risk of assault, robbery and rape when looking for a private place to go the toilet.

People felt that they were being treated as if they were not human. They felt that the conditions were deliberately being made so difficult, even life threatening, to force them to accept forced removal out of the city to what people called the ‘human dumping grounds’. They felt that the government was saying that if we wanted a formal house and water, sanitation and electricity we must accept exclusion from the city. But people were not willing to accept forced removal to places 30 or 40 kilometres outside of the city because there were no opportunities for livelihoods there, no good schools and when there was transport it was very expensive. We saw the forced removals as a new kind of segregation, this time taking impoverished people out of the cities.

At the time the government had a policy of ‘eradicating slums’. They promised that there would be no more ‘slums’ by 2014. When they ‘eradicated a slum’ they came with guns. They came like they were coming for a war. Some people would be left homeless and others would be taken to tiny and badly made ‘houses’ far outside of the cities, in the ‘human dumping grounds’. People called these houses ‘dog kennels’.

We organised to stop the evictions. We were successful in this. We also organised to stop the ‘slum eradication’ program. We were also successful in this. We organised ourselves to arrange clean ups and we brought ’Operation Khanyisa” (self-connection to electricity) which started in Soweto to Durban. A few people were already connecting themselves but in a disorganised and sometimes dangerous way. We organised self-connections across whole settlements in a safe and well organised manner with properly insulated and buried cables. We were also able to organise more taps and even some toilets by connecting ourselves to the plumbing infrastructure. At the same time we struggled for the state to provide electricity, more taps, toilets and paths. We eventually succeeded in overturning the ban on the provision of electricity to shack settlements and the Municipality agreed to begin providing ablution blocks to settlements (they also drained the pit latrines in Kennedy Road). However provision has been too slow. We also won an agreement that settlements in well located areas, like Kennedy Road, would be upgraded in a participatory way rather than destroyed and people either left homeless or forcibly removed to the human dumping grounds.

However, this agreement was not implemented. The ANC cannot accept that housing can be provided outside of its control. The tenders, the jobs and the allocation of the houses all go through party structures to sustain the power of the party over the people. This is one of the reasons why we were attacked and driven out of the Kennedy Road settlement by the ANC, acting with the support of the police, in 2009.

We continue to occupy new lands, to provide our own infrastructure where possible, to struggle for settlements to receive services from the municipality and for participatory upgrades.

We have faced serious repression in our struggle including assault, slander, arrest, torture, imprisonment and murder. Basic rights, like the right to protest, have been denied to us. It is not just the state that wants impoverished people to remain in our dark corners while others speak for us and decide for us. Some NGOs and academics have also thought that they have a right to speak for us and to decide for us. They have also behaved in a repressive way.

Just a week ago an eThekwini Parks and Cemeteries official visited one of our settlements called George Hill in Sydenham. George Hill is well located on privately owned land less than 10 km from the Durban CBD. They have no toilets and no water stand pipe. Just below the settlement there is a small public park and a little pool with fish inside. The official was very angry blaming residents for urinating and toileting under the trees there. She claimed that all this dirt flows to the pool to kill the fish. She made several calls from the police to the councillors’ office and to Abahlali. When I had a telephone conversation with her she made it clear that she did not care about the fact that residents do not have toilets but she was more worried about the fish and the ‘public park ’that is being messed up.

Again I was quickly reminded that the impoverished do not count in our city, as she saw no problem with blaming people without sanitation for the situation rather than blaming the fact that some residents of the city still do not have sanitation. It did not bother the official that residents were refused water and sanitation. She did not care if they have to grow their children in this environment. Instead she threatened to have them evicted through the private landlord who also said he does not want those residents on his property. For this official an eviction, an armed eviction, was a good solution. She wanted to remove impoverished people from their place in the city instead of making sure that they had a dignified and safe place in the city.

We have noticed that many university intellectuals talk about the land struggles as if they are only rural struggles. But the urban land struggle is an important part of the land struggle. Land and housing are one of the major challenges facing our growing cities. Our cities continue to be highly contested as the cities fail to absorb and accommodate many of their habitants. Impoverished people continue to be governed with violence, nepotism and corruption. While we are told a lot about the shortage of land in urban centres we continue to successfully identify and occupy those unused vacant lands to give some space in the city for the oppressed. Our movement has always called for the social value of land to come before its commercial value. We have successfully stopped many evictions in this city through resistance in the courts, in communities and on the streets. We have also participated into people’s urban planning and people’s governance. We have identified and challenged problems with policy. We have exposed corrupt and vicious councillors including the two who are today serving life sentence in Westville prison for killing an Abahlali activist in the KwaNdengezi area.

The impoverished continued to be impoverished and excluded from nation building in post-apartheid South Africa. It has become clear that we do not count in our society. Our role is just to vote for our poverty and to obey politicians and some NGOs. It is taken as a crime for us to organise ourselves, to think for ourselves and to speak for ourselves. We do not have these entirely basic infrastructures simply because we are not recognised as human beings. There is no other reason. We all saw how quickly the stadiums were built in 2010. If our lives were taken seriously we would not be forced to continue living as we do.

State democracy does not work for us. It is for these reasons that we have started organising outside the state and its ruling party. We organise autonomously from all political parties and NGOs.

We acknowledge the fact that there is now rolling out of containers containing water and sanitation and showers (ablution blocks) in our shack settlements. We also see electricity being rolled out in some of the selected settlements. We acknowledge that some settlements will now be upgraded rather than destroyed. We welcome this progress. But we remind everyone that this progress comes from the struggles waged and won by the shack dwellers and other impoverished people. We remind everyone of the cost of these struggles – including murder.

Abahlali aims to build the power of the impoverished from below. We know our exclusion and oppression is not a question of budget constraints and priorities. It is a question of justice. Our organising calls for inclusive cities, for cities for all, irrespective one’s socio-economic situation. We are well aware that it was the struggles of the people of this country that allowed the ANC to return from prison, exile and the underground. We are very confident in the political capacities of oppressed people. The only democracy we enjoy today is the democracy we have built for ourselves. The water and connections to electricity that we enjoy today are services we have provided for ourselves. And yes, the lands that we have successfully occupied and where we have built our lives are ours as a result of our struggle and resistance and we pride ourselves to it.

The eThekwini municipality has a budget of over 46 billion. It cannot justify its failure to provide electricity, water and sanitation in all the shack settlements in our city and to being working with people in shack settlements to plan participatory upgrades so that the impoverished can live a dignified life. We live as we do not because there is a shortage of land or money. We live as we do because we are not counted as human. Therefore at the heart of our struggle there is a duty to defend our humanity.

* S’bu Zikode is a founder member of the shack dwellers organisation, Abahlali baseMjondolo Movement SA.

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to [email=[email protected]]editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org[/email] or comment online at Pambazuka News.