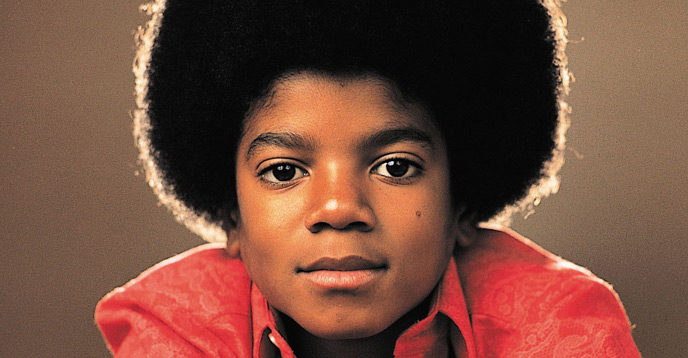

The man in our mirror: Michael Jackson

In the wake of Michael Jackson's death, Greg Tate discusses the entertainer's place in the pantheon of black American musical greats. Considering his immense cultural significance within American political and cultural life, Tate stresses that Jackson 'came to rank as one of the great storytellers and soothsayers of the last 100 years'. Regardless of his alienation from the black America of his origins, Tate argues, Jackson remained a devoted student of black music, dance and style, taking and giving back in unparalleled ways.

What black American culture – musical and otherwise – lacks for now isn't talent or ambition, but the unmistakable presence of some kind of spiritual genius, the sense that something other than or even more than human is speaking through whatever fragile mortal vessel is burdened with repping for the divine, the magical, the supernatural, the ancestral. You can still feel it when you go hear Sonny Rollins, Ornette Coleman, Aretha Franklin, or Cecil Taylor, or when you read Toni Morrison – living Orishas who carry on a tradition whose true genius lies in making forms and notions as abstract, complex and philosophical as soul, jazz or the blues so deeply and universally felt. But such transcendence is rare now, given how desperate, soul-crushing and immobilising modern American life has become for the poorest strata of our folk, and how dissolute, dispersed and distanced from that resource-poor but culturally rich, heavyweight strata the rest of us are becoming. And, like Morrison cautioned a few years ago, where the culture is going now, not even the music may be enough to save us.

The yin and yang of it is simple: You don't get the insatiable hunger (or the black acculturation) that made James Brown, Jimi Hendrix and Michael Jackson run, not walk, out the hood without there being a hood – the Olympic obstacle-course incubator of much musical black genius as we know it. As George Clinton likes to say, 'Without the humps, there's no getting over.' (Next stop: hip-hop – and maybe the last stop too, though who knows, maybe the next humbling god of the kulcha will be a starchitect or a superstring theorist, the Michael Jackson of D-branes, black P-branes, and dark-energy engineering.) Black Americans are inherently and even literally 'damaged goods', a people whose central struggle has been overcoming the non-person status we got stamped and stomped into us during slavery and post-Reconstruction and which resonates even now, if you happen to be black and poor enough (as M-1 of Dead Prez wondered out loud, 'What are we going to do to get all this poverty off of us?'). As a people, we have become past-masters of devising strategies for erasing the erasure. Dreaming up what's still the most sublime visual representation of this process is what makes Jean-Michel Basquiat's work not just ingenious, but righteous and profound. His dreaming up the most self-flagellating erasure of self to stymie the erasure is what makes Michael Jackson's story so numbing, so macabre, so absurdly Stephen King.

The scariest thing about the Motown legacy, as my father likes to argue, is that you could have gone into any black American community at the time and found raw talents equal to any of the label's polished fruit: The Temptations, Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder, Smokey Robinson, or Holland-Dozier-Holland – all my love for the mighty D and its denizens notwithstanding. Berry Gordy just industrialised the process, the same as Harvard University or the CIA (Central Intelligence Agency) have always done for the brightest prospective servants of the evil empire. The wisdom of Berry's intervention is borne out by the fact that since Motown left Detroit, the city's production of extraordinary musical talent can be measured in droplets: the Clark Sisters, Geri Allen, Jeff Mills, Derrick May, Kenny Garrett, J Dilla. But Michael himself is our best proof that Motown didn't have a lock on the young, black and gifted pool, as he and his siblings were born in Gary, Indiana: a town otherwise only notable for electing our good brother Richard Hatcher to a 20-year mayoral term and for hosting the historic 1972 National Black Political Convention, a gathering where our most politically educated folk (the Black Panther Party excepted) chose to shun Shirley Chisholm's presidential run. Unlike Motown, no one could ever accuse my black radical tradition of blithely practicing unity for the community, or of possessing the vision and infrastructure required to pull a cat like Michael up from the abysmal basement of America and groom him for world domination.

Motown saved Michael from Gary, Indiana – no small feat. Michael and his family remain among the few Negroes of note to escape from the now century-old city, which today has a black American population of 84 per cent. These numbers would mean nothing if we were talking about a small Caribbean nation, but they tend to represent a sign of the apocalypse where urban America is concerned. The Gary of 2009 is considered the 17th most dangerous city in America, which may be an improvement. The real question of the hour is, how many other black American men born in Gary in 1958 lived to see their 24th birthday in 1982, the year Thriller broke the world open louder than a cobalt bomb and remade black American success in Michael's before-and-after image? Where black modernity is concerned, Michael is the real missing link, the 'bridge of sighs' between the Way We Were and What We've Become in what Nelson George has astutely dubbed the 'post-Soul Era' – the only race-coded 'post' neologism grounded in actual history and not puffery. Michael's post-Motown life and career are a testament to all the cultural greatness that Motown and the Chitlin circuit wrought, but also all the acute identity crises those entities helped set in motion in the same funky breath.

From Compton to Harlem, we've witnessed grown men break down crying in the hood over Michael, some of my most hard-bitten, 24/7 militant black friends – male and female alike – copped to bawling their eyes out for days after they got the news. It's not hard to understand why, for just about anybody born in black America after 1958 – and this includes kids I'm hearing about who are as young as nine years old right now – Michael came to own a good chunk of our best childhood and adolescent memories. The absolute irony of all the jokes and speculation about Michael trying to turn into a European woman is that after James Brown, his music (and his dancing) represent the epitome – one of the mightiest peaks – of what we call black music. Fortunately for us, that suspect skin-lightening disease, bleaching away his black-nuss via physical or psychological means, had no effect on the field-holler screams palpable in his voice, or the electromagnetism fuelling his elegant and preternatural sense of rhythm, flexibility and fluid motion. With just his vocal gifts and his body alone as vehicles, Michael came to rank as one of the great storytellers and soothsayers of the last 100 years.

Furthermore, unlike almost everyone in the Apollo Theater pantheon save George Clinton, Michael now seems as important to us an image-maker – an illusionist and a fantasist at that – as he was a musician and entertainer. And until Hype Williams came on the music-video scene in the mid-1990s, no one else insisted that the visuals supporting R&B and Hip Hop would be as memorable, eye-popping and seductive as the music itself. Nor did anyone else spare any expense to ensure that they were. But Michael's phantasmal, shape-shifting videos, were also, upon reflection, strangely enough his way of socially and politically engaging the worlds of other real black folk from places like South Central Los Angeles, Bahia, East Africa, the prison system and Ancient Egypt. He did this sometimes in pursuit of mere spectacle ('Black and white'), sometimes as critical observer ('The way you make me feel'), sometimes as a cultural nationalist romantic ('Remember the time'), even occasionally as a harsh American political commentator ('They don't care about us'). Looking at those clips again, as millions of us have done over this past weekend, is to realise how prophetic Michael was in dropping mad cash to leave behind a visual record of his work that was as state-of-the-art as his musical legacy, as if he knew that one day our musical history would be more valued for what can be seen as for what can be heard.

George Clinton thought the reason Michael constantly chipped away at his appearance was less about racial self-loathing than about the number-one problem superstars have, which is figuring out what to do when people get sick of looking at your face. His orgies of rhino- and other plasties were no more than an attempt to stay ahead of a fickle public's fickleness. In the 1990s, at least until Eminem showed up, Hip Hop would seem to have proven that major black pop success in America didn't require a whitening up, maybe much to Michael's chagrin.

Whatever Michael's alienation and distance from the black America he came from – from the streets, in particular – he remained a devoted student of popular black music, dance and street style, giving to and taking from it in unparalleled ways. He let neither ears nor eyes nor footwork stray too far out-of-touch from the action, sonically, sartorially or choreographically. But whatever he appropriated also came back transmogrified into something even more inspiring and ennobled than before. Like the best artists everywhere, he begged, borrowed and stole from (and/or collaborated with) anybody he thought would make his own expression more visceral, modern and exciting, from Steven Spielberg to Akon to, yes, okay smartass, cosmetic surgeons. In any event, once he went solo, Michael was, above all else, committed to his genius being felt as powerfully as whatever else in mass culture he caught masses of people feeling at the time. I suppose there is some divine symmetry to be found in Michael checking out when Barack Obama, the new King of Pop, is just settling in: Just count me among those who feel that, in Michael Jackson terms, the young orator from Hawaii is only up to about the Destiny tour.

Of course, Michael's careerism had a steep downside, tripped onto a slippery slope, when he decided that his public and private life could be merged, orchestrated and manipulated for publicity and mass consumption as masterfully as his albums and videos. I certainly began to feel this when word got out of him sleeping in a hyperbaric chamber or trying to buy the Elephant Man's bones, and I became almost certain this was the case when he dangled his hooded baby son over a balcony for the paparazzi, to say nothing of his alleged darker impulses. At what point, we have to wonder, did the line blur for him between Dr Jacko and Mr Jackson, between Peter Pan fantasies and predatory behaviour? At what point did the Man in the Mirror turn into Dorian Gray? When did the Warholian creature that Michael created to deflect access to his inner life turn on him and virally rot him from the inside?

Real soul men eat self-destruction, chased by catastrophic forces from birth and then set upon by the hounds of hell the moment someone pays them cash-money for using the voice of God to sing about secular adult passion. If you can find a more freakish litany of figures who have suffered more freakishly disastrous demises and career denouements than the black American soul man, I'll pay you cash-money. Go down the line: Robert Johnson, Louis Jordan, Johnny Ace, Little Willie John, Frankie Lymon, Sam Cooke, James Carr, Otis Redding, Jimi Hendrix, Al Green, Teddy Pendergrass, Marvin Gaye and Curtis Mayfield. You name it, they have been smacked down by it: guns, planes, cars, drugs, grits, lighting rigs, shoe polish, asphyxiation by vomit, electrocution, enervation, incarceration, their own death-dealing preacher-daddy. A few, like Isaac Hayes, get to slowly rust before they grow old. A select few, like Sly, prove too slick and elusive for the tide of the River Styx, despite giddy years mocking death with self-sabotage and self-abuse.

Michael's death was probably the most shocking celebrity curtain-call of our time because he had stopped being vaguely mortal or human for us quite a while ago, had become such an implacably bizarre and abstracted tabloid creation, worlds removed from the various Michaels we had once loved so much. The unfortunate blessing of his departure is that we can now all go back to loving him as we first found him, without shame, despair or complication. 'Which Michael do you want back?' is the other real question of the hour. Over the years, we've seen him variously as our Hamlet, our Superman, our Peter Pan, our Icarus, our Fred Astaire, our Marcel Marceau, our Houdini, our Charlie Chaplin, our Scarecrow, our Peter Parker and black Spider-Man, our Ziggy Stardust and Thin White Duke, our Little Richard redux, our Alien vs. Predator, our Elephant Man, our Great Gatsby, our Lon Chaney, our Ol' Blue Eyes, our Elvis, our Frankenstein, our ET, our Mystique, our Dark Phoenix.

Celebrity idols are never more present than when they up and disappear, never ever saying goodbye, while affirming James Brown's prophetic reasoning that 'Money won't change you. But time will take you out.' Brown also told us, 'I've got money, but now I need love.' And here we are. Sitting with the rise and fall and demise of Michael, and grappling with how, as Dream Hampton put it, 'The loneliest man in the world could be one of the most beloved.' Now that some of us old-heads can have our Michael Jackson back, we feel liberated to be more gentle toward his spirit, releasing him from our outright rancour for scarring up whichever pre-trial, pre-chalk-complexion incarnation of him first tickled our fancies. Michael not being in the world as a Kabuki ghost makes it even easier to get through all those late-career movie-budget clips where he already looks headed for the out-door. Perhaps it's a blessing in disguise, both for him and for us, that he finally got shoved through it.

* Greg Tate is a writer for The Village Voice.

* This article was originally published by blackpower.com.

* Please send comments to [email protected] or comment online at http://www.pambazuka.org/.