Legendary Kenyan TV journalist Sir Mohinder's memoir is a riposte

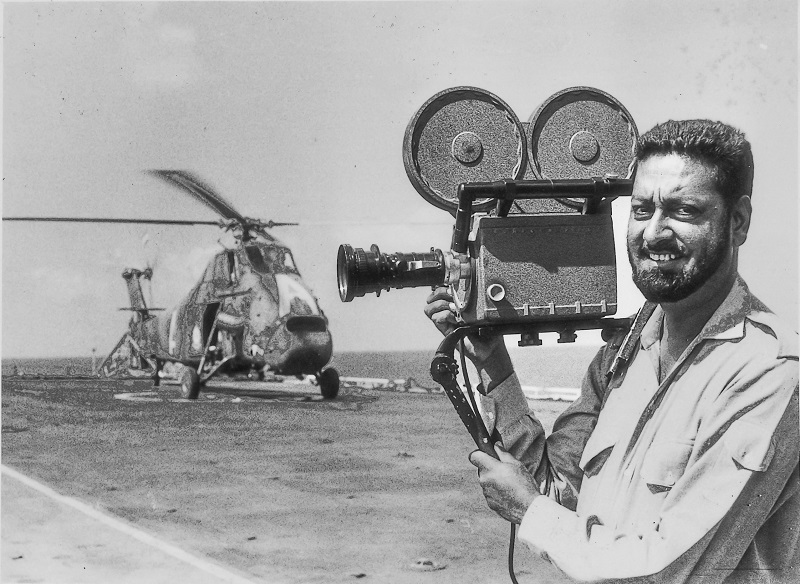

My Camera, My Life details the extraordinary life of a brilliant and daring TV journalist and filmmaker who covered some of the most significant events in modern history, more so in Africa. The legendary Sir Mohinder is the gentle giant of television journalism in this part of the world.

In 1947, a young Indian boy from Punjab Province docked at the port of Mombasa, the Kenyan coral island perched on the Indian Ocean. He disembarked from a lumbering Khandala, the ship he had boarded 14 days before in Bombay. He was accompanied by his father, then an employee of the East African Railways, his mother, and siblings. He was a stripling 16-year-old, bubbly, tall, and full of adventure. The boy’s name was Mohinder Singh Dhillon, who in the fullness of time would awe us all, as one of the greatest TV cameramen of the 20th century, so much so that in 2005 he was knighted as “Knight Commander” by Emperor Haile Selassie’s grandson, His Highness Crown Prince Zere Yacob Asfa Wossen Haile Selassie, heir to the throne.

In 1947, a young Indian boy from Punjab Province docked at the port of Mombasa, the Kenyan coral island perched on the Indian Ocean. He disembarked from a lumbering Khandala, the ship he had boarded 14 days before in Bombay. He was accompanied by his father, then an employee of the East African Railways, his mother, and siblings. He was a stripling 16-year-old, bubbly, tall, and full of adventure. The boy’s name was Mohinder Singh Dhillon, who in the fullness of time would awe us all, as one of the greatest TV cameramen of the 20th century, so much so that in 2005 he was knighted as “Knight Commander” by Emperor Haile Selassie’s grandson, His Highness Crown Prince Zere Yacob Asfa Wossen Haile Selassie, heir to the throne.

Sir Mohinder was honoured because of his “outstanding contribution to humanity” and for “having performed, through newsreel photography, the distinguished humanitarian service of bringing to the attention of the world community critical issues affecting the welfare of the African continent.” Just a year before Sir Mohinder’s admission into knighthood, his long time friend and colleague at ITN TV, celebrated TV journalist Jon Snow had written in his autobiography, Shooting History: A Personal Journey, that Sir Mohinder “was a brilliant but understated cameraman.”

Born in 1931, Sir Mohinder Dhillon grew up in Babar Pur, a dusty village hidden in sand dunes, famed for her buffaloes, which families like Sir Mohinder’s kept for milk. His paternal uncle, a doctor, had wanted him to take after his vocation. But Mohinder loved sports and fighting. He drew particular satisfaction whenever his bull cock, Raja, which he fitted with spikes, would smash his rivals at cock-fighting. He could aerially maneuver his kite and destroy the opponent’s! In Punjab, the language of instruction in school was Urdu, but when the family moved to Kenya, the children were now forced to learn a new language, English, which was the language used in school. It was going to be difficult.

“I knew I would be leaving school without even the most basic educational qualifications. Looking around, I felt disconsolate and useless,” Sir Mohinder writes in his memoir My Camera, My Life, one of the most extraordinarily evocative memoirs ever to be written. “In a simple gesture, my father gave me a basic second-hand camera. This was the ‘poor man’s Rolleiflex’ with a fixed speed and fixed aperture. Neither he nor I knew it at the time, but this simple gift marked the beginning of a 60-year-long career in photography.”

At around the same time, Sir Mohinder came across an essay on photography in a magazine. So moving was this essay that the impressionable Mohinder promised himself to try, on his camera, everything the essayist, Indian photographer I.S. Johar, had done. At that time Mohinder was producing miniature photos at home. Then came the godsend opportunity to take his apprenticeship in the darkroom of Edith Haller’s Halle studio situated in a chemist shop; Mohinder had gone there to seek an accountant’s job but he landed himself a job in the studio which he later bought out: “I was determined to show I was both capable and eager to learn.”

His tutor Peter Howlett, a subdued racist, did not think so. Howlett would have kicked Mohinder out, but for Ms Haller, who employed him anyway! Mohinder’s first opportunity to prove himself as a professional photographer was at a time when Howlett was absent, and the assignment had come from the East African Standard, then Kenya’s only daily newspaper, which wanted Halle studio to send a photographer to cover a horse race. Mohinder’s shots were beautiful, and thus began a long and distinguished career in photojournalism.

Such was the humble beginning of the legendary frontline TV cameraman and filmmaker Sir Mohinder Dhillon. During those heady days Sir Mohinder made friends with Ivor Davis, the Fleet Street-trained newspaper journalist who had come to Kenya in 1958 to work with the East African Standard, and who had introduced Sir Mohinder to the cut-and-thrust of the global media. Ivor quit Standard in 1960 and in 1961 he teamed up with Sir Mohinder to found the iconic television news agency Africapix Media, the first such news photography and media agency in East and Central Africa. “Television, then still in its infancy, as a news medium, was expanding fast, creating a new global market for film footage, not least from Africa,” says the legendary Sir Mohinder of those heady days.

Sir Mohinder has had a brush with death on several occasions. In 1960, he was arrested and deported from South Africa with the warning he would be shot should he try any monkey tricks with his camera. Sir Mohinder’s mistake was that he had taken photos of a bloodied Dr Hendrik Verwoerd, apartheid’s architect, who had just survived an assassination attempt.

In 1964, Sir Mohinder came very close to being executed in Congo during the Stanleyville Hostage crisis. He was arrested and frog-marched to the firing squad where people suspected to be sympathisers of the Simba Rebels, the disgruntled supporters of the slain Patrice Lumumba, were being executed by government soldiers. Sir Mohinder had flown to Congo during the civil war with experienced news reporter Andrew Borovic of Associated Press to cover the American-sponsored rescue mission dubbed ‘Operation Dragon Rouge. Twice he was arrested: first as he filmed, from the forest, soldiers executing people on a bridge and tossing them in the river. The films were destroyed, before he was handed back his camera and released. That was a prelude to his second arrest: Sir Mohinder’s passport had the treasonable Albertville visa, a region once held by rebels. When he was frog-marched to the firing squad scene, there were about 50 people, who would be riddled with bullets one by one. Then only 33 years old, but already a household name in television, Sir Mohinder was rescued by the ITN TV crew of Sandy Gall, Jon Lane and Eric Vincent, who arrived at the scene when only an ill-fated handful was remaining. He remains supremely grateful to these journalists.

Told under the backdrop of the Cold War era, Sir Mohinder’s memoir is a riposte to the criminal mission of the West in the Congo; the plundering and looting of Congo’s vast minerals, and gung ho foreign mercenaries’ massacres. Then, it was Moise Tshombe, the quisling blue-eyed boy, who was embedded in the criminal activities of notorious Irish mercenary kingpin Mike Hoare. One wonders how these foreign mercenaries could be allowed to turn Congo into a theatre of war if indeed the intention was not to provide a corridor for smugglers of that country’s minerals. Hoare wrote about his exploits, so did Sir Mohinder’s colleague, war correspondent Hans Germani in his book, White Soldiers in Black Africa. Are there parallels in what is happening in South Sudan today? We have been told that the internecine civil war in that country is about the ruling Dinka and the opposition Nuer. So, the problems in South Sudan must be seen through a jaundiced ethnic prism. But South Sudan has vast oil reserves too, at which many an outsider salivate!

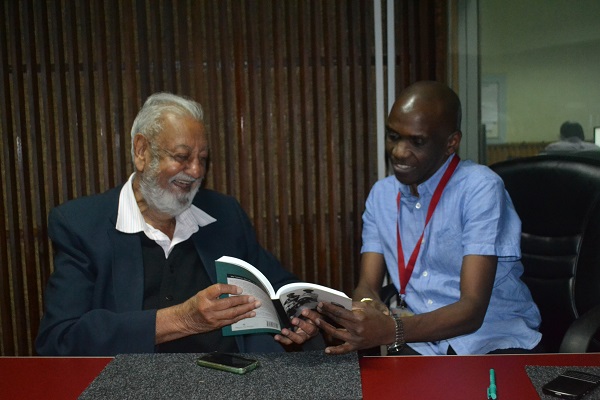

Reading Sir Mohinder’s memior, talking to him, peering through his library is refreshing. A towering figure of a man, he delighted the KBC staff when he visited Broadcasting House for the third and final part of the special series of The Books Café: “I was here when this building was being unveiled,” he says referring to one of the administration blocks, and thus confirming that indeed, the legendary photojournalist has been omnipresent in the public affairs of Kenya.

A brilliant but unassuming TV journalist and filmmaker, Sir Mohinder has covered some of the most significant and historic events in modern history, more so in Africa. He began his extraordinary career as a news and current affairs programmes TV journalist. He then went into documentary filmmaking, feature films, becoming Director of Photography (DOP). Sir Mohinder witnessed the rise and fall of many African leaders. His illuminating eye-witness accounts of presidents Jomo Kenyatta, Julius Nyerere, Milton Obote, William Tubman, Siad Barre, Idi Amin, Gaafer Numeiri, Muammar Gaddafi, Robert Mugabe, and his reminisces of Emperor Haile Selassie, as his official photographer and filmmaker, the Emperor’s imminent downfall and subsequent arrest, are rare biographical tomes into the lives of these African leaders.

Sir Mohinder worked as Emperor Haile Selassie’s official photographer for eight years travelling with the emperor in more than 40 countries. He sometimes felt his conscience pricked that he was propagating the emperor at a time when he had lost touch with common people. Yet when Emperor Haile Selassie was deposed, Sir Mohinder was in Ethiopia and recorded the events firsthand as they unfolded. The Marxist Provisional Military Committee of Mengestu Haile Mariam, later to be known as the Derg, who deposed Emperor Haile Selassie handed him a prepared statement, the thrust of which was that the Emperor had resigned. Sir Mohinder writes in his memoir, My Camera, My Life, that what struck him on that day was Emperor Haile Selassie’s personal remark delivered with grace after reading and discarding the recorded statement.

Then 82 years, Emperor Haile Selassie was gallant and magnanimous with his tormentors: “If the revolution is good for the people of Ethiopia, then I too am for the revolution. And if I am shown to have been an impediment to progress in Ethiopia, then I shall be the first to acknowledge my want of judgment, while bearing no ill-will towards those responsible for dethroning me.”

Under the circumstances, Sir Mohinder says that this statement, redolent of the centuries-old imperial throne, which must have caught the Marxists unawares, was “a particularly noble and courageous parting shot.” Did the lives of ordinary Ethiopians improve under the Derg?

As a frontline news cameraman and filmmaker, Sir Mohinder went to remote and oftentimes dangerous places around the world to cover stories and film documentaries. Many times he risked his life doing investigative journalism, shooting civil war, and filming capricious tyrants. In 1967 he was to earn himself the sobriquet, Death-Wish-Dhillon while covering the Yemen Civil War on the streets of Aden, where he could capture in the same frame of his camera warring combatants, thus acquiring a feat in war reportage yet unsurpassed.

Among Sir Mohinder’s documentaries are: African Calvary, Vietnam After the Fire, Elephant Run, The Tulip Elephants, No Easy Walk, We are The Children, Khomeini’s Other War, The Shifta War, etc. “I made my name in documentary filmmaking, that’s where my fame came from, because news after 24 hours is forgotten, but if you make a good documentary, its forever,” Sir Mohinder says.

Sir Mohinder went to Vietnam in 1988, a little more than 10 years after the Vietnam War to shoot the documentary, Vietnam After the Fire. He had been there briefly in 1970 and 1971 as the war ranged. But as John Pilger, the award-winning Australian war correspondent would write, most of the news from Vietnam was heavily censored, articles were clipped to remove the sharp edges in a story, or were not published outright, and worse the journalists, ‘junketeers’, did not just write the story! So, a documentary such as Sir Mohinder’s would bring to world attention the horror and devastation left behind by the invading America’s use of chemical weapons, such as the infamous Agent Orange, and the oxygen sapping Napalm B. Still, the Vietnamese humiliated America, thereby undermining its Cold War strategy. However, the country left behind by the defeated American army was, in the words of Sir Mohinder, a little more than “a wasteland - of dead and dying forests, and of poisoned soils and streams, all eerily silent and devoid of living organisms.”

John Pilger has written in his bestselling book, Heroes (1986) about America’s war crimes in Vietnam: “…the longest campaign in the history of aerial bombardment. Few outsiders saw its effects on the civilian population (my italics) of the North. I was one who did. Against straw and flesh was sent an entirely new range of bombs, from white phosphorous to anti-personnel devices which discharged thousands of small needles.”

Elsewhere, these wanton atrocities of genocidal magnitude would call for criminal war trials in The Hague, but this was America! When the US stormed central Vietnam, writes Pilger, there were no Vietcong (guerrillas). Instead, they were met by “curious children” and “beautiful girls wearing silk dresses split at the waist offering posies of flowers. The press photographers, and film crews recorded this moving illusion of welcome while the jungles and highlands beyond cast a blood-red shadow no one saw.”

The Vietnamese were master guerrilla fighters. America’s defeat, no different from the earlier defeats of Chinese, Japanese, and French armies by the diminutive Vietnamese, buoyed South Africa’s liberation hero Oliver Tambo as to send ANC combatants to be trained by the Vietnamese, to drink from their tenacity, to learn their strategy, hence forcing the mighty Apartheid regime on to the negotiating table.

Sir Mohinder’s memoir is a collector’s souvenir of modern history. Are there lessons to be learned? During the Cold War, America used black propaganda to justify its invasions of countries, to destabilise these countries, to prop up their stooges. Nigeria and West Africa should find the unspoken motive of America’s enthusiasm to ‘help’ them fight Boko Haram insurgents.

Sir Mohinder shot a documentary on the Shifta War between Kenya and Somalia. He went to the Iranian Kurdistan regions to document a people’s plight. He went to Afghanistan in 1990 as a civil war simmered there.

In 1982 Sir Mohinder survived a helicopter crash in Tanzania shooting a documentary, but not without a broken arm, and a chronic spine injury. In 1983, he together with BBC reporter David Smith was among the first journalists to open the lid on the Ethiopian famine that was already ravaging the country. Sir Mohinder’s footage in one of the earliest refugee camps showed “appalling scenes of hunger, disease, suffering and despair.” Sir Mohinder and Smith had somehow outmaneuvered Mengestu Haile Mariam who had tried very hard to suppress any news of the famine.

In 1984, barely one year later, Sir Mohinder’s erstwhile friend, renowned photographer Mohamed Amin, would splash this story around the world and earn plaudits. Young Mohamed Amin – he was 18 years when Sir Mohinder first met him - had been trained in TV photography by Sir Mohinder before moving to form Camerapix in mid-1960s.

Sir Mohinder relates at least three incidents that fanned the famed animosity between him and Mohamed, to be summed up as “sabotage,” “wiliness” and “fraudulence,” especially, in regard to the documentary, African Calvary, a title given to Sir Mohinder by Mother Teresa, having flown with her to Ethiopia. African Calvary was a documentary based on the two photographers’ footages of the 1984 Ethiopian Famine. When they discussed the film, they agreed that Sir Mohinder would do filming in Africa while Amin would film interviews with world leaders in Europe and America.

When the documentary was ready, and Sir Mohinder was invited to London to preview before sanctioning its airing, he was shocked to find his name clipped out, yet his African footage had been used! That’s the straw that broke the camel’s back! Sir Mohinder relates these events without bitterness in his evocative and poignant memoir, My Camera, My Life. He writes:

“Where sabotage has occurred, it has invariably been perpetrated by ambitious, glory-seeking individuals bent on serving, not the organisations they work for, but only themselves and their own inflated egos.”

Perhaps it was the buffalo milk he drank as a young boy in Babar Pur village in India, or the resilience of his Sikh ancestors, that kept him strong in the face of wily, malicious saboteurs and fraudulent men and women, some who ripped him off. His humility and pursuit for equal rights is guided by his Sikh religion: “Sikhism teaches you to defend the dignity of women and all human beings,” he says. It was his father who imbued in him the virtue of caring for others: “My son, if you live for yourself, it is not living; if you live for others that is living a meaningful life.”

Sir Mohinder’s early news and currents affairs footages were taken by ITN TV. His documentary films were for BBC and ZDF among other media houses.

Sir Mohinder is an ardent human rights activist and environmentalist. Now 85, he spends his time reading, writing, and keeping abreast with what is happening. “I admire the courage of the reporters in Syria,” he told me on The Books Café, the premier literature programme which I host every Saturday at 2pm on KBC English Service radio. “If I were to be born again, I would do the same thing: news, current affairs and documentary filmmaking.”

Here is a one of the greatest journalists who walked these grounds! As ITN TV’s Jon Snow avows, “you cannot write about Sir Mohinder without first mentioning his fundamental humanity - his loyalty, steadfastness, loveliness. Put simply, Sir Mohinder is a rock. In the field, he was my mentor – somebody without whom I might never have progressed in television news.”

A warm, delighting, humane man with a fearless persona, the legendary Sir Mohinder is the gentle giant of television journalism in this part of the world. With a career spanning six decades, Sir Mohinder has worked with some of the most illustrious journalists of his generation: Sir Robin Day, Ivor Davis, Sandy Gall, Hans Germani, Jon Snow, David Smith, Richard Vaughan. Without wanting to be didactic, Sir Mohinder Dhillon’s My Camera, My Life is a lesson in journalism - photography, news, interview, commentary, features, and documentary. Sir Mohinder’s memoir is the 2016 book of the year.

* Khainga O’Okwemba is the President of PEN Kenya Centre, a poet, journalist, essayist, and presenter of the premier literature programme The Books Café on KBC English Service.

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to [email=[email protected]]editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org[/email] or comment online at Pambazuka News.