Pan-Africanism: I am dreaming of course

Mwalimu Nyerere professor of Pan-African Studies at the University of Dar es Salaam, interviews Bereket Habte Selassie, an observer and participant in African politics for almost five decades. From the first All Africa People’s Conference in 1958, to the ‘doubt’ and ‘desperation’ of the current African reality, Selassie provides a thoughtful perspective on the history Pan-Africanism, as well as advice for the future of the African Union. This interview first appeared in Pan-African journal Chemchemi.

INTRODUCTION

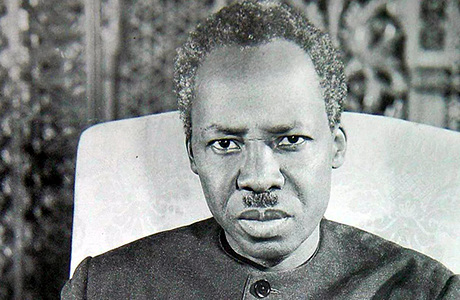

Professor Bereket Habte Selassie has the distinction of observing and participating in African politics for almost five decades. He was trained in Britain and then joined the service of the Ethiopian government in 1958. In 1962, at the age of 30, he was appointed by Emperor Haile Selassie to be the attorney general of Ethiopia. He participated in the Africa People’s Conferences organised by Kwame Nkrumah and in the formation of the OAU. In 1962 when the Emperor unilaterally scrapped the federation with Eritrea and sent his army to occupy Eritrea, Bereket Selassie resigned to join the Eritrean freedom movement. Later, following Eritrea’s liberation, he chaired the constitutional commission and drafted Eritrea’s constitution, which was never adopted by the Eritrean government. In this interview with Issa Shivji, Habte Selassie reminisces on his impressions of the Pan-African Movement.

ISSA SHIVJI: Thank you very much for agreeing to do this interview for the Chemchemi, Bereket. You have had the distinct honour of living through and participating in some momentous events in the Pan-Africanist history of our continent. You were present both at the first All Africa People’s Conference in 1958 called by Kwame Nkrumah and also at the founding of the Organisation of African Unity (the predecessor of African Union) in Addis Ababa in 1963. Tell us of the mood of African leaders and their views, opinions, positions on creating a United States of Africa at the 1958 Conference. Did the idea look realistic then? More or less realistic than today?

BEREKET HABTE SELASSIE: As you mentioned, I was indeed privileged to have been present at those events. But before I answer your specific questions, let me begin by making reference to the current African reality, very briefly. The reality today is such that even the most optimistic of men – and I am one of them – find it hard to banish feelings of doubt, if not desperation.

Though I remain optimistic, in view of the prevailing African reality, my optimism is tinged with a dose of scepticism. Africans of my generation were involved in what I can only call a romance with Africa, from the heady days of the independence era through four decades of neo-colonial exploitation, invariably accompanied with protests – protests against domestic dictatorships and continuing poverty as the rich few got richer and the greater mass of the poor populations got poorer.

In these circumstances, to continue in a state of romantic engagement with the continent would have implied wilful refusal to accept the reality, in the hope of transforming it. It is admirable to make attempts at transformation but, on the whole, there have been no meaningful changes. In fact, as the French say, plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose [the more things change the more they stay the same].

It brings to mind the story of Sisyphus in Greek legend, pushing a boulder up the hill, forever trying to climb to the top, and forever failing. Such seems to be the fate of our benighted continent. I have not abandoned hope; but there must be a limit to optimism. As Antonio Gramsci famously opined, the pessimism of the intellect is a good corrective to the optimism of the will.

Now let me turn to the glorious days of the independence era when most Africans of my generation agreed with Kwame Nkrumah’s vision of a United African Continent. The first time this was brought home to me as a distinct possibility was at the All African People’s Conference in Accra, Ghana, in December 1958.

The conference was convened by the indefatigable and inimitable Nkrumah, who had tried to persuade his brother African heads of state and government a few months earlier to agree to the creation of continental unity. He had just published his book, Africa Must Unite, and was gathering a group of young Pan-Africanists, using Ghana’s not inconsiderable wealth, to help liberation fighters throughout the continent.

Some of the best known were Patrice Lumumba of Congo and Felix Moumie of Cameroun. Both were Pan-Africanists and both were martyred. Lumumba was a victim of a joint CIA and Belgian conspiracy. Moumie was poisoned by an agent of the French Intelligence Service.

Nkrumah’s All African People’s Conference was designed to bring pressure to bear on the government leaders by mobilising labour unions, the youth, women’s organisations and leaders of liberation movements. We should remember that in 1958 there were only seven independent African States; and none of their leaders except perhaps Guinea’s Sekou Toure, was in favour of a Pan-Africanist vision of uniting the continent. It was clear that Nkrumah’s was a lonely voice. But the sentiment of the political forces outside government seemed to be on his side at the time. As always happens, once they attain governmental power, former liberation leaders forget, or at least modify their previously held view about African unity. Personal power grounded in a colonially-derived nation state structure militated against the ideal of African unity. Once ensconced in national state power, even former Pan-Africanists like Leopold Sedar Senghor of Senegal, whose concept of Negritude contained elements of Pan-Africanism, changed. Even the regional experiment of a Mali federation that he had championed earlier was abandoned as personal rivalry between him and his Malian comrade, Mamadou Dia, vitiated its realisation.

Clearly, in all cases, personal power at the state level trumped the Pan-Africanist ideal. That has become the dominant political reality.

http://www.pambazuka.org/images/articles/427/where_is_uhuru.gif

ISSA SHIVJI: In your article in Societies without Borders (volume 2-1 2007) you say that you were very impressed by the camaraderie between sub-Saharan and North African leaders at the 1958 conference. Again, you allude to the fact that North African leaders like Nasser of Egypt and Ahmed Ben Bella of Algeria were received with great enthusiasm and reverence at the 1963 founding conference of the OAU. In the light of the oft-repeated claim – even by some African intellectuals – made these days that unity of black states south of the Sahara and Arab states in the North is untenable, how do you see, understand and explain that historical precedence compared with present-day perceptions?

BEREKET HABTE SELASSIE: In the heady days of the independence movements when the Algerian revolution was embraced as part of the African revolution, and some of us even entertained the notion of going there and fighting for it (perhaps foolishly), there was no division between black Africa and Arab Africa, or between the ‘Arab’ North and the ‘black’ South. The Algerians were regarded as African heroes by most Africans of my generation. Similarly, as Ben Bella’s speech at the founding conference of the OAU eloquently expressed it, the Algerians considered the liberation struggle in the rest of Africa as part of their struggle.

The ideology of the Algerian liberation front (the FLN), with its socialist orientation and internationalist stand, also provided a point of solidarity and unity with the struggle in the rest of Africa. You may remember the Martiniquian doctor, (author of the famous The Wretched of the Earth) Frantz Fanon, was accepted as one of their own by the FLN leaders. In fact he led the Algerian delegation at the Accra conference. As it happened, our delegation and theirs stayed in the same hotel and we chatted a lot as I happen to speak French.

As for the Egyptian leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser, his strategy of anti-imperialism was framed within the concept of Egypt’s three circles – African, Arab, and Islamic. These three circles were the defining elements of his strategic and geopolitical goals. But, though this goal was expressed in his unstinting help to African liberation movements, there were times when the three circles tended to create contradictions and problems. At times, black Africans who went to Cairo for help might have felt neglected or sidelined. But on the whole, there was good reception. It is not easy when you don’t understand the language and culture of the country from which you seek aid.

So on the whole, in the halcyon days, there was better mutual understanding and accommodation between North and South. Changing economic and social conditions have negatively affected that relation. People and governments tend to be less generous during economic hardship. We should never lose sight of this. When a country is in a better economic condition, it behaves more generously, as illustrated by the behaviour of Libya’s leader Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and his record of the last few years, including his push to reform the OAU and help create the African Union (AU). I would say that we need to have a broader view of things when we consider relations between North and South in Africa. While we cannot ignore history and some differences of culture, we need to accept our North African brothers and sisters as fellow Africans and do our best to create conditions for fostering mutual acceptance and cooperation. To that end, we need to define some minimal common goals and start with those, beginning with culture and trade.

ISSA SHIVJI: In relation to the above, how do you see Nkrumah’s own attitude? Was there an undercurrent of this type of tension then?

BEREKET HABTE SELASSIE: I have never heard Nkrumah utter a word that in any way showed any reservation regarding our North African brothers and sisters. Nor have I read any writing of his to that effect. On the contrary, the fact that he married an Egyptian woman shows the opposite to be the case. Nkrumah and Nasser respected each other as fellow socialists, even though Nkrumah’s socialism was a little more to the left – his organisational principles were grounded on Leninist precepts, as he often cited Lenin as a supreme teacher on questions of party organisation. Where he parted company with Lenin (and Marx) was in his insistence on the application of the African cultural heritage. His Pan-Africanism was influenced more by W. E. Dubois. But it embraced the entire continent and did not make a distinction between North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Whether there were hidden tensions in the application of that principle of unity of North and South it is hard to tell. In any case, all relationships involve tension of one kind or another—even domestic relations, among siblings.

ISSA SHIVJI: You describe in interesting detail the founding of the OAU and Nkrumah’s attitude towards it. Nkrumah, you recall, would have walked out had it not been for the intervention of Emperor Haile Selassie through Sekou Toure. In the light of your experience of over half a century of the independence of African states within colonial borders, how do you rate Nkrumah’s vision of the United States of Africa?

BEREKET HABTE SELASSIE: There are two ways of answering this question. One is by reference to what I stated in the introduction, that is to say, to judge Nkrumah’s vision in hindsight, from the perspective of the sorry sate of affairs in Africa today. In that sense, Nkrumah may be characterised as a failed prophet, vainly proselytising and chasing rainbows, rather like Don Quixote round the wind-mills. That, I am sure, is how his adversaries would paint him. To Pan-Africanists, however, he was a true prophet who battled mightily to impress upon his brethren the historic necessity of African unity if Africa were to secure her rightful place in the family of nations - if she is to face the rest of the world united and stronger, both politically and economically. The artificially created colonial borders that define African nation-statehood, which the OAU reaffirmed in Cairo in 1964, need to be revisited in all seriousness.

Let me conclude the answer to this question by saying that Nkrumah’s warning still rings in my ears when he said, ‘Unless we are united politically, we will be for ever vulnerable, subject to economic exploitation by the powerful economies of the world’. Those were prophetic words, and globalisation has made Africa even more vulnerable today than before. I think these words of Nkrumah, which sum up Africa’s predicament, should be written in golden letters at the entrance of the African Union as a reminder of our sad condition, and young Africans should be exposed to the ideas of African unity in every way possible. In this task we academics bear a special responsibility. We can certainly take a leaf from the experience of Europe of the last fifty-odd years, though I don’t think we have to wait fifty years to achieve the end of African unity.

ISSA SHIVJI: And how would you assess the two major trends – those who advocate gradualism and those who insist on political unity ‘now, now’? (By the way, during Nkrumah’s time too we had those two trends represented by Nyerere and Nkrumah!)

BEREKET HABTE SELASSIE: Realistically speaking, the regional economic organisations that we have today may be used as building blocks for eventual unity. But the ultimate goal should be unity in accordance with Nkrumah’s vision. That is how I see his relevance in our times. I am aware that the two approaches were also present in the 1960s. In fact it was Mwalimu Nyerere’s eloquence and popularity with the majority of African leaders, who were opposed to Nkrumah’s vision, that defeated Nkrumah’s idea of continental unity at the time when the issues were debated at the first and second OAU summit meetings.

This is an area where we can learn from the mistakes of other regions of the world. It took Europe some fifty years to create the European Union (EU). They did it in stages. In 1968, they established the European Economic Community (EEC), under the Treaty of Rome. The original signatories of the Treaty of Rome (France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg), agreed to form a customs union, adopt a common external tariff, and harmonise their domestic economic policies.

They made it clear that their ultimate goal was a common market embracing all of Western Europe. In 1973, Great Britain, Ireland and Denmark joined in, followed by Greece in 1981, and Spain and Portugal in 1986, bringing the number up to twelve. Thus in a matter of thirty years, the EEC became the second largest economic power in the world. By 1992, the EEC had created a common market, and within the next decade, Europe achieved the dream of centuries, transforming itself into the European Union, bringing into its membership several former allies of the USSR.

Africa has had its experience of regional cooperation, such as the East African Economic Community patterned on the EEC and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Despite the multiplicity of regional groupings, however, there has been slow progress towards economic integration. What has been missing from the very beginning is the political will and cooperative vision.

ISSA SHIVJI: Finally, you have spent over three decades of your life in the Eritrean freedom struggle. How do you see such conflicts on the continent in relation to Pan-Africanism? Some argue that such conflicts precisely dictate a gradual process of unification so that individual countries can put their houses in order, so to speak, before we think of unification. Others argue the opposite: That only Pan-African political unity has the potential to resolve inter-African conflicts.

BEREKET HABTE SELASSIE: The debate as to which is the best way to achieve the aim of African unity will probably go on for generations. It took Europe centuries; I hope we don’t have to wait that long. The case for Pan-Africanist unity can be made in different ways. Opponents of Eritrea’s case for independence, influenced by Emperor Haile Selassie’s diplomacy (powerfully backed by the United States), used to argue that recognizing Eritrea’s case would open a ‘Pandora’s Box’ in African politics by inspiring other groups within constituted nations to seek secession.

To put the case in perspective, a brief historical background is necessary. As you know, the Eritrean case was grounded in legal and historical arguments that should have resonated with the African post-colonial rationale. According to that rationale all former colonial territories defined by the colonially-fixed boundaries constitute the post-colonial nation-state. In other words, African leaders accepted the colonial legal order created under the Berlin Conference; they confirmed it as the post-colonial legal order by passing the Cairo Resolution (of the OAU) in 1964.

The Eritrean argument was that the application of that rationale should extend to the case of Eritrea because Eritrea is an entity created by the same colonial history as the rest of Africa. There is a very interesting statement made by former Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, who recognised the same rationale long before the Cairo Resolution. He said that, though the Eritreans had a just case, American strategic and geopolitical interests in the region dictated that Eritrea should be given to the US ally, Ethiopia.

Thus the convergence of American interest and Emperor Haile Selassie’s expansionist ambition sealed Eritrea’s fate. It was only after peaceful, diplomatic means to exercise their right to self-determination failed that the Eritrean people took up arms: what was denied them diplomatically, they achieved by force of arms, after thirty years of a bloody war.

Now, the Americans used the UN forum to achieve their strategic objective. At their behest, the UN passed a Resolution joining Eritrea with Ethiopia under a lopsided federal arrangement in which Eritrea had a modicum of regional autonomy. But at least the UN legal instrument creating the federation recognised Eritrea as an autonomous entity, and Eritreans accepted the fait accompli hoping to retain their autonomous identity within the federation. The Emperor’s vaulting ambition overreached itself, and he abolished the federation and imposed an imperial rule. That was the origin of the war of independence. That, incidentally, was also the point at which I resigned from his government and eventually joined up with the Eritrean liberation struggle.

Many Ethiopians, including some of my friends who were anti-imperial in their ideology, had hoped that the Eritrean autonomy would inspire other regions of Ethiopia to gain a measure of autonomy and thus transform the empire eventually into a sort of a commonwealth of willing partners. What the current government of Ethiopia originally set out to do is an approximation of that vision. Whether it can be sustained is another matter. The two governments of Eritrea and Ethiopia (based on the EPLF and TPLF respectively) are led by former comrades-in-arms who fought jointly, defeating Mengistu’s army. Much hope was pinned on their promise to establish a progressive regional government based on cooperative principles that would be a model for the rest of Africa. It proved to be a vain hope. Indeed, they not only failed to create a regional cooperation; in 1998, they fought a deadly and futile war that took the lives of over 100,000 people and much devastation of property.

This conflict, among others, seems to lend credence to the argument that each country has to put its own house in order before thinking of unity with others. But then waiting for each country to do that is like waiting for Godot, if I may be melodramatic. I still maintain that we need to hold Nkrumah’s vision aloft and work towards its realisation in various ways, perhaps through stages of regional groupings. In this the AU may need to act more vigorously to prod regions and countries to create regional trade relations. The AU needs also to tap into African resources at two levels:

1. At the level of wise elders tapping on the African genius of mediation and peace building to resolve conflicts; and

2. At the level of experts, tapping on increasing African expertise in all technical fields related to trade and commerce, culture and other areas.

The recent experience of conflict in Kenya provides an example of an extreme case of tribally-based conflict centred on, or exacerbated by, competition over resources. In the present instance, the competition was for political power which has become an all important resource. In the final resolution of the Kenya conflict, an exemplary model of mediation was provided by the role of the Tanzanian President, if my information is correct. The Kenya example reminds me of an interesting phrase of British historian John Lonsdale. Writing about the artificial creation of ‘tribes’ by the colonial authorities, he described the effect of that division as the ‘conversion of negotiable ethnicity into competitive tribalism.’

This useful insight is helpful in all attempts to create structures that can restore the original ethos of negotiating and mediation in place of deadly competition. In such endeavour, Pan-Africanism may need to be redefined to accommodate new modes of thinking derived from research and creative writing. Our poets, as much as our historians and sociologists, have to weigh in on this Herculean task.

I am dreaming, of course!

* This article first appeared in the maiden issue of CHEMCHEMI, Bulletin of the Mwalimu Nyerere Professorial Chair in Pan African Studies of the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and is reproduced here with the kind permission of the editorial board of CHEMCHEMI.

* Bereket Habte Selassie has observed and participated in African politics for almost five decades.

* Issa Shivji is the Mwalimu Nyerere professor of Pan-African Studies at the University of Dar es Salaam.