Challenges of teacher education in Tanzania

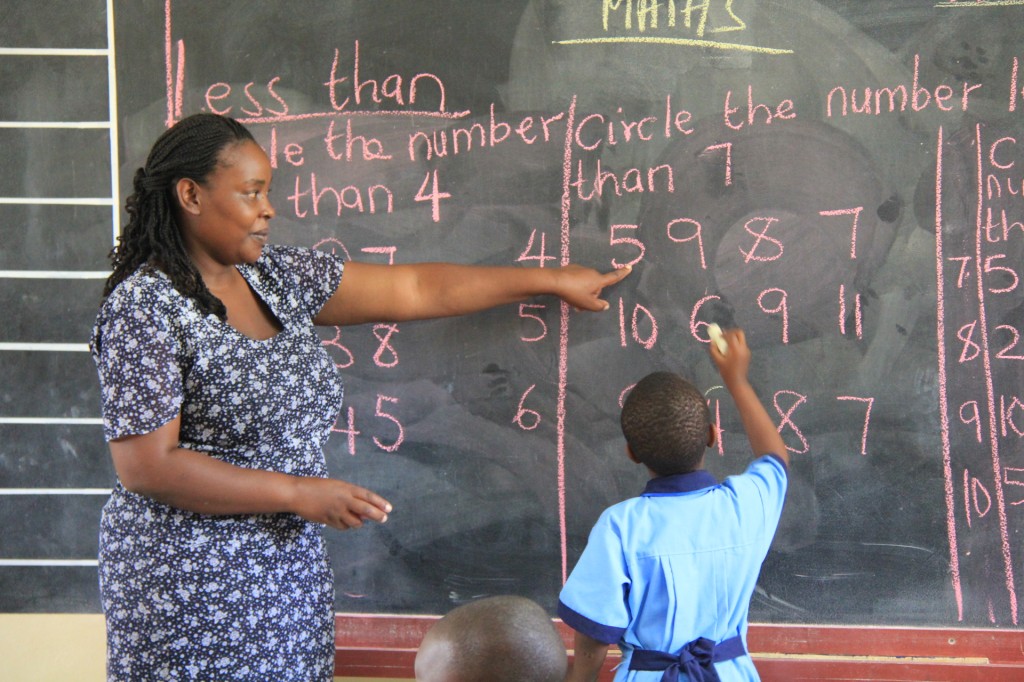

Tanzania’s famous founding president Julius Nyerere was a teacher. But despite the government’s commitment to education in its development agenda, many young people shun the teaching profession. Salaries are low, classes big and teaching has little prestige among the professions.

The concept of education

Education as concept can be used to convey two different though complementary meanings. In one sense it is used to refer to the extent, measure or level of cumulative attainment by an individual of a distinctive quality of information, knowledge and/or understanding that places the individual above the average person. In another sense, education is seen as a dynamic, on-going process that involves a person in several things at the same time: acquiring and assimilating information from source, physically and mentally processing the information acquired and transmitting the processed information to others or applying the acquired skills to different situations in an attempt to solve different problems and challenges of existence (Nyirenda & Ishumi, 2008).

Education in Tanzania

The formal education and training system in Tanzania comprises two years of preprimary education, seven years of primary education, four years of junior secondary, two years of senior secondary and three or more years of tertiary education. On the whole, the education system can be divided into three levels: Basic, secondary and tertiary. The basic level education consists of pre-primary, primary, and non-formal adult education. The secondary education level includes the ordinary and advanced levels of schooling, while tertiary level programs are offered by higher institutions, including universities and teacher training colleges

Ministry of education

The Ministry of Education and Vocational Training has general responsibility for education. Amongst other aspects, the ministry is charged with quality assurance, research, monitoring and evaluation of primary and secondary education. In addition to the ministry, various other parties are involved in the governance and monitoring of education services, such as the prime minister's office, the regional administration and local government, various NGOs and individuals coordinated by the central government.

Statistics from the Ministry of Education show that 400,000 youth complete primary education each year. Out of those only 10% get the opportunity to continue with secondary education in both government and private schools: 42,157 complete secondary education each year. Only 10,000 youths secure places in higher institutions of learning including universities each year (Ministry of Labour and Youth Development, 1996). In Tanzania schools, colleges and private sectors institutions provide opportunities to youth. In this way, some of the youth who miss the opportunity to join higher education can join private and government teacher training colleges (TTCs).

Teacher training

Teacher training in Tanzania is currently offered in three levels, which are grade A, diploma and degree level. Grade A student teachers are trained at teacher training colleges to equip them with knowledge, pedagogical skills and methods to teach at primary schools. The training lasts two years that include teaching practice. If the student teachers complete their training successfully they graduate as professional teachers and are employed by the government to teach in primary schools. However, there are some cases particularly in rural areas where these teachers teach in secondary schools because of shortage of teachers especially in science subjects. Diploma student teachers are trained to teach at secondary schools. Training also lasts two years. Degree level teacher students are trained at the universities for three years to teach at secondary schools and teacher training colleges.

In many countries, including Tanzania, teachers get no further additional professional support for a long time, leading to ineffective teaching, hence, poor performance in schools (Mbunda , 1998). Pointing out the importance of life-long learning for teachers Mbunda states that:

“Pre-service training alone is not enough whether one acquires a teacher certificate or a first degree for the basic reasons that;

- A single teacher training course is not sufficient to keep one intellectually alive;

- Curriculum always changes and knowledge and teaching technology develop and;

- Education is a life-long and continuous process”.

Teacher professional development

Teacher development is the process and activities designed to promote professional knowledge, skills and attitudes of teachers for the purpose of improving pupils’ learning (Guskey, 2000). The purpose of professional development in education is to build and transform strong knowledge through teachers with the ambition to achieve excellence in education (Compoy, 1997). Gaible and Burns (2005) assert that in order to be effective, teachers’ professional development should address the core areas of teaching content, curriculum, assessment and instruction.

According to Education and Policy Training in Tanzania (1995), teacher professional development constitutes an important element for quality and efficiency in education. Teachers need to be exposed regularly to new methodologies and approaches of teaching. The teaching effectiveness of every serving teacher will thus need to be developed through planned and known schedules of in-service training programmes. Therefore, in-service training and re-training shall be compulsory in order to ensure teacher quality and professionalism.

The effectiveness of the teacher depends on her competence (academically and pedagogically) and efficiency (ability, work load, and commitment), teaching and learning resources and methods; support from education managers and supervisors (Rogan 2004; Van den Akker & Thijs 2002; Mosha 2004). Teacher professional development provides opportunities for teachers to explore new roles, develop new instructional techniques, refine their practice and broaden themselves both as educators and as individuals.

Factors influencing teacher professional development

Villegas-Reimers (2003) identifies conceptual, contextual and methodological factors on how change, teaching, and teacher development are perceived. Contextual factors refer to the role of the school leadership, organizational culture, external agencies and the extent to which site-based initiatives are supported. Methodological factors relate to processes or procedures that have been designed to support teacher professional development. It would seem that from the perspective of an interactive system model, teacher professional development is a function of the interaction between and among five key players or stakeholders. These are the ministry responsible for teacher education, universities, schools, the community and the teachers themselves. In the context of Tanzania the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training is responsible for providing policy and financial support for teacher professional development. Universities and teacher colleges are responsible for providing training, conducting policy oriented research and providing relevant literature and materials to support teachers in schools.

The teacher’s perception of the professional development is the most important of all factors. It is an intrinsic motivation, an internal force. The teacher has to see and accept the need to grow professionally. A teacher who perceives professional development positively is eager to attain new knowledge, skills, attitudes, values and dispositions. Within such dispositions there is pride, self–esteem, team spirit, commitment, drive, adventure, creativity and vision. All these attributes have to be owned by the teacher (Mosha 2006). Teacher’s perception depends on self-evaluation, the influence and support of school leadership and school culture (Komba & Nkumbi, 2008).

In Tanzania, there are various opportunities that youth can take advantage of such as leadership, job skills, vocational training and health. For instance, there are programs like The Life Choices targeting youth aged 10-19 with the core message of sexual abstinence and being faithful to prevent HIV infection. This programme is realistic because it does not only offer youth health education but also skills training, parental/teacher/community support, recreational activities, sports and youth camps.

Youth opportunities are also available in the teaching profession. The minimum admission requirement for the teacher education certificate course is Division III of the Certificate of Secondary Education Examination while for a diploma teacher certificate one requires Division III in the Advanced Certificate of Secondary Education Examination (ETP, 1995: 48). Following liberalisation policies in 1994, individuals and private agencies were encouraged to invest in education to complement government efforts. A number of private education institutions and colleges have been established in the country at all levels of the education system, but with limited enrolment capacity.

There are various challenges that hinder young people from joining the teaching profession in Tanzania. First, teaching is perceived negatively by young people because of low salaries in comparison to other professions like law and medicine. In addition, teachers are not respected in the society as before (Mosha, 2016). Complaints from the teachers about poor teaching and learning environment, shortage of resources and large class sizes do not attract young people to the profession. Second, the teaching profession is not a choice for many youth but they join it because they have no alternative. Third, youth perceive teaching profession as the profession joined by those who did not perform well in the national examinations.

It can be concluded that education is a key component of the government of Tanzania’s development agenda but has not attracted young people to join the teaching profession because it is always perceived negatively compared to other professions.

* MARY A. MOSHA teaches at in the Faculty of Education, University of Bagamoyo.

References

Compoy, R. W. (1997). Creating effective instruction models in professional development in school. Professional Education Journal, 19(2) pp 32-42.

Educational system in Tanzania: Challenges and prospective. Retrieved on 5th 2017 from http://www.tanzania.go.tz/educationf.html.

Gaible, E. & Burns, (2005). Using technology to train teachers: Appropriate use of ICT for teacher professional development in developing countries. Washington: The World Bank.

Guskey, T. R. (2000). Evaluating professional development. California: Thousand Oak, Corwin Press Inc.

Komba, W. L & Nkumbi, E. (2008). Teacher professional development in Tanzania: Perceptions and practices. Journal of International Cooperation in Education, Vol.11 No.3 (2008) pp.67-83.

Mbunda, F. L (1998). Management workshop for Teachers’ Resource Centres. Dar es Salaam: Institute of Kiswahili Research.

Ministry of Labour and Youth Development (1996). National, Youth Development Policy. Dar es Salaam.

Mosha, H. J. (2004). New Direction in teacher education for quality improvement in Africa. Papers in Education and Development, 24, 45-68.

Mosha, H. J. (2006). Capacity of school management for teacher professional development in

Tanzania. Delivered at a workshop on the role of universities in promoting basic education in Tanzania, held at the Millennium Towers Hotel, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, May 19.

Mosha, M. (2016). Secondary school students’ attitudes towards teaching profession: A case of Tanzania. Research Journal of Educational Studies and Review Vol. 2 (5), pp. 71-77.

Nyirenda, S, D. & Ishumi, A.B.G (2008). Philosophy of Education: An introductory to concepts, principles and practice. Dar es Salaam: Dar es Salaam University Press.

Rogan, J. (2004). Professional development: Implications for developing countries. In K. O-saki, K. Hosea & W. Ottevanger, Reforming science and mathematics education in sub-Saharan Africa: Obstacles and opportunities (pp.155-170). Amsterdam: Vrije Universteit Amsterdam.

Salesian Missions (2017). Giving hope to millions of youth around the world Globe. New York: New Rochelle.

United Republic of Tanzania (1995). Educational training policy. Dar es Salaam: Adult Education Press.

Villegas-Reimers, E. (2003). Teacher professional development: An international review of literature. UNESCO: International Institute for Educational Planning. Retrieved on June 2017 from http://www.unesdoc.unesco.org/images