Women’s rights: Looking back or moving forward?

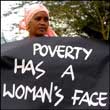

Despite the wide adoption of protocols for gender equality across Africa, ‘violations of women’s human rights have reached epidemic proportions,’ Mary Wandia writes in Pambazuka News, ‘and unless we adopt a multi-sectoral approach in the implementation and monitoring of regional and international commitments, we shall continue to marginalise half of the continent’s population.’ With the Beijing +15 Africa Review meeting underway in Banjul, Wandia asks whether Africa’s ministers for gender and women will ‘rise up to the challenge’.

2009 is a significant year in the African women’s rights calendar. The assembly of the African Union declared 2010-2020 the African Women’s Decade. The summit called on member states, AU organs and regional economic communities to support the implementation of Decade activities.[1]

The declaration comes when women worldwide mark the 30th anniversary of the United Nations (UN) Convention on elimination of all forms of discrimination against women (CEDAW) in 2009. Later in 2009, Africa’s ministers for gender/women will meet in Banjul, the capital of Gambia to review the implementation of the Beijing Platform in Africa during the last 15 years.

In 2010, women worldwide will mark 15 years since the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing (Beijing + 15). African women will be marking six years since the adoption of the Solemn declaration on gender equality in Africa (SDGEA) and five years since the Protocol to the African charter on human and people’s rights on the rights of women in Africa entered into force. But in 2009, it is clear that women’s lives have not yet seen the promise of the continental framework.

THE CURRENT STATUS OF WOMEN IN AFRICA

WHAT WE’VE ACHIEVED

Africa now has its first female head of state, Her Excellency Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the president of Liberia. Women’s representation in national parliaments has improved in a majority of African countries. Africa has the highest reported rate of progress – 10 per cent – on this target in the world over the period 1990 to 2007. But the story is not all together cheerful, as several countries have shown only a slight improvement over the period 2003-2007.[2] Many factors still hinder women’s political participation, such as political parties being slow to respond to women’s interest, under-investment in women candidates’ campaigns, cultural barriers, and conflicting demands on the time of women candidates due to their domestic and social responsibilities.

African governments have established various mechanisms at different levels –including national machineries – to mainstream gender in the formulation of policies, plans and programmes, policy advocacy and to monitor and evaluate the implementation of international, regional and national commitments. Particular attention has been given to the formulation of national gender policies and implementation plans, with some countries having prepared sector-specific gender policies.

However, the mechanisms for the integration of gender equality and women’s empowerment remain weak at all levels, lacking adequate capacity, authority and funding. Line ministries have not reached gender equality targets due to low levels of resource allocations. Gender concerns continue to be treated rhetorically or as separate women’s projects. Sex-disaggregated data and information from gender-sensitive indicators are often not collected. When they are collected, they are lost in aggregation of published data or not used.[3]

OBSTACLES TO EQUALITY

The democratic recession in Africa has seen cultural and religious fundamentalism. This has resulted in the enactment of laws that curtail citizen, civil society and media freedoms, the adoption of and implementation of discriminatory laws and discrimination and attacks against sexual minorities, which individually and combined affect the advancement of women’s rights in Africa. In addition, threats to lives of human rights defenders and infringements of freedoms of association that impact the promotion, realisation and enjoyment of human rights and women’s rights are on the rise.

While states have failed to fulfil their commitments, they are undermining regional and international standards by introducing anti-human rights bills. Several governments have adopted or are in the process of adopting discriminatory legislation reversing fundamental women’s rights including, but not limited to, bills on criminalisation of HIV, indecent dressing laws and anti-homosexuality bills. These bills violate various rights: The right to privacy and confidentiality, the right to sexual integrity and autonomy, the right to bodily integrity, freedom from discrimination, the right to health, the right to equal protection before the law, freedom of association, sexual and reproductive rights, freedom of choice, the right to life etc.

The continent is experiencing a rise in food prices far beyond the reach of the poor in the context of global, food, energy and financial crises further exacerbated by climate change. Due to their subordinate position in society, a large number of African women have borne the brunt of these crises, further exacerbating their already precarious situation. In sub-Saharan Africa, agriculture accounts for approximately 21 per cent of the continent's GDP and women contribute 60-80 per cent of the labour used to produce food both for household consumption and for sale.[4] However, women face discrimination under both customary and formal systems as a result of culturally embedded discriminatory beliefs and practices, male control of inheritance systems, and the spread of HIV/AIDS, which further weakens land rights and livelihood options of widows and orphans.[5]

Latest updates confirm that, at primary school level, most African countries are likely to reach gender parity by 2015. However, the impressive improvement in gender parity in primary education is not mirrored in secondary education, where there is still significant under-representation of girls. Limited education and employment opportunities for women in Africa reduce annual per capita growth by 0.8 per cent. Had this growth taken place, Africa’s economies would have doubled over the past 30 years.[6]

A vast majority of African countries are experiencing a negligible improvement in maternal mortality rate. Without a major leap forward, Africa is off-track to meet this goal.[7]Half of all maternal deaths globally (265,000) occur in sub-Saharan Africa. Haemorrhage alone causes 34 per cent of maternal deaths. Yet most of these conditions could be prevented or treated with good quality reproductive health services, antenatal care, skilled health workers assisting at birth, and access to emergency obstetric care.[8]

The proportion of women infected with HIV is high and increasing. As of December 2007, women constitute 61 per cent of infected people in the four sub-regions except North Africa. In almost every country in the region, prevalence rates are higher among women than men. The vulnerability of African women and girls to HIV infection is integrally linked to underlying gender inequalities, societal norms and discrimination.[9]

Violence against women and girls has remained one of the most widespread violations of human rights in our continent. Violence – or the threat of it – not only causes physical and psychological harm to women and girls, it also limits their access to and participation in society because the fear of violence circumscribes their freedom of movement and of expression as well as their rights to privacy, security and health.

Systematic rape has left millions of women and adolescent girls traumatised, pregnant, or infected with HIV.[10] However, in the face of high levels of violence, women and girls’ access to the justice system is limited by legal illiteracy, lack of resources and, gender insensitivity and bias of law enforcement agents.

Although African women are disproportionately affected by conflict compared to men, their voices in conflict prevention, post-conflict reconstruction, transitional justice and peace building process are only faintly listened to, often leaving them at the margins of peace processes. This is in spite of the international and regional commitments on gender equality in peace processes.

BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN POLICY AND REALITY: WHAT CAN BE DONE?

There is an urgent need to renew commitment to gender equality and the empowerment of women and to take concrete steps to address the gaps between commitment and implementation. This will not happen without a paradigm shift to a multi-sectoral approach to ensure the implementation and monitoring of women’s rights commitments made at regional and international levels.

The United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) has developed a multi-sectoral framework that could accelerate implementation of women’s rights commitments at national level if embraced by governments.[11] Solidarity for African Women’s Rights (SOAWR) believes that this framework forms the basis for implementing existing commitments and accelerating real changes in the lives of African women and girls.

According to UNIFEM, gender inequalities that disempower women cut across all sectors, from health, economy, labour, agriculture and food security, to education, security and justice. No one sector can provide a comprehensive response. A multi-sectoral framework proposed by UNIFEM emphasises the need for women’s rights targets – based on regional and international instruments – to be integrated in national development plans and strategies, including growth and poverty reduction strategies and budgets. UNIFEM is quick to note that the multi-sectoral approach has been used in other areas such as in the response to the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Countries have been able to mobilise all sectors of governments, private sector, faith-based organisations and civil society, leading to significant gains in public awareness of the pandemic and a decrease in the level of stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV/AIDS.

Promoting the realisation of rights and empowerment by women is a national priority in its own right, because of its importance for the achievement of other national priorities including economic growth and poverty reduction. The multi-sectoral approach premise draws from the principle that all organs of government have obligations under the treaties ratified by a country as well as other commitments in declarations. Each organ and department of government is thus responsible and accountable for women’s rights falling within its mandate.

The multi-sectoral approach proposes a comparable division of roles. For instance, the ministry of labour would provide leadership in making progress on the obligation of government to take all measures to eliminate discrimination against women in the field of employment. The ministry of agriculture or rural development would address relevant women’s rights issues: Secure land tenure, access to and control over land, access to extension services and markets for produce. The ministry of health has responsibility to ensure the right to health of women – including sexual and reproductive health – is respected and promoted. The judiciary would ensure the implementation of regional and international commitments through application in constitutions and other provisions of law. The police would be obligated to investigate and prosecute violations of women’s rights promptly.

Overall coordination would be done by a government agency that has gender and human rights technical capacity to provide backstopping services, and at a level or status of power and influence within the overall government system, that is well respected and is backed up by resources. Existing gender machineries could be strengthened to play this role. Governments already have inter-ministerial coordination mechanisms that may be expanded to include coordination of the implementation of human rights commitments. The coordination mechanism is key to developing or reviewing a national policy and action plan on achieving women’s rights and clarifying respective roles and commitments of the various sectors and budgetary allocations to integrate women’s rights into sector programmes. Monitoring progress and regular flow of information between different government agencies helps to facilitate a comprehensive approach to women’s rights, developing training programmes, identifying gaps and contributing to regular country reports required by regional and international institutions.

Violations of women’s human rights have reached epidemic proportions and unless we adopt a multi-sectoral approach in the implementation and monitoring of regional and international commitments, we shall continue to marginalise half of the continent’s population. Will African ministers of gender/women rise up to the challenge?

BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Mary Wandia is the gender justice and governance lead at Oxfam GB’s Pan Africa programme. She writes here in a personal capacity.

* Mary Wandia acknowledges generous comments and inputs from Neelanjana Mukhia, Muthoni Wanyeki, Gichinga Ndirangu, Jessica Horn, Sabine Herbrink, Faiza Mohamed, Naisola Likimani, Nelly Maina, Norah Matovu Winyi, Daniela Rosche and Irungu Houghton.

* Please send comments to [email protected] or comment online at Pambazuka News.

NOTES

[1] Decision on the African Women’s Decade – Assembly/AU/Dec. 229(XII)

[2] Gender parity in decision-making has advanced the most in Rwanda (48.8 per cent), Mozambique (34.8 per cent), South Africa (32.8 per cent), Tanzania (30.4 per cent), Burundi (30.5 per cent), Uganda (29.8 per cent), Seychelles (29.4 per cent), Namibia (26.9 per cent), Tunisia (22.8 per cent), Eritrea (22 per cent) and Ethiopia (21.9 per cent).

[3] Seventh African Regional Conference on Women (Beijing +10) Decade Review of the Implementation of the Dakar and Beijing Platforms for Action: Outcome and the Way Forward Addis Ababa, 12-14 October 2004 http://www.uneca.org/beijingplus10/outcome_and_way_forward.htm

[4] http://www.fao.org/docrep/X0250E/x0250e03.htm#TopOfPage

[5] FAO ‘Agrarian Reform, Land Policies and the Millennium Development Goals: FAO’s Interventions and Lessons Learned During the Past Decade’, ARC/06/INF/7 (2006)

[6] ‘Gender and Economic Empowerment in Africa’, a paper presented to the 8th Meeting of the Africa Partnership Forum in Berlin, Germany on 22-23 May 2007. www.africapartnershipforum.org

[7] Angola, Burundi, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Malawi, Nigeria, the Niger, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Somalia.

[8] United Nations, The Millennium Development Goals Report 2009 pp. 27

[9] African Union Commission and United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Assessing Progress in Africa towards the Millennium Development Goals Report 2008. March 2008. E/ECA/COE/27/10 AU/CAMEF/EXP/10(III) P. 15

[10] UNAIDS, UNFPA, UNIFEM, Women and HIV/AIDS: Confronting the Crisis. Geneva, New York. 2004. 47-48

[11] This section summarises the Multi-Sectoral Approach Guide developed by UNIFEM ‘Fast-tracking Implementation of the AU Protocol on Women’s Rights and CEDAW in Africa.

REFERENCES

Africa Partnership Forum, ‘Gender and Economic Empowerment in Africa’, a paper presented to the 8th Meeting of the Africa Partnership Forum in Berlin, Germany on 22-23 May 2007. www.africapartnershipforum.org

African Union Commission and United Nations Economic Commission for Africa Assessing Progress in Africa towards the Millennium Development Goals Report 2008. March 2008. E/ECA/COE/27/10 AU/CAMEF/EXP/10(III)

Communiqué of the ‘Stakeholders Meeting on Domestication and Implementation of the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa’, 16 – 18 July 2009, Kigali, Rwanda organized by SOAWR, UNIFEM and the AU Gender Directorate and the Communiqué of the SOAWR Annual Review and Agenda-Setting Workshop, Theme: ‘Spreading our Wings: A Multi-Sectoral Approach to Women’s Rights’ 5-7 October 2009, Panafric Hotel, Nairobi, Kenya http://www.soawr.org/en/

Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa www.africa-union.org/

Solemn Declaration on Gender Equality in Africa http://www.uneca.org/beijingplus10/outcome_and_way_forward.htm

UNAIDS, UNFPA, UNIFEM, Women and HIV/AIDS: Confronting the Crisis. Geneva, New York. 2004.

UNIFEM, 2005 Progress of the World's Women 2005: Women, Work and Poverty United Nations, The Millennium Development Goals Report 2009 pp. 27

WHO 2004. ‘Violence Against Women and HIV/AIDS: Critical Intersections: Sexual violence in conflict settings and the risk of HIV’. Information Bulletin Series, Number 2, November 2004

World Bank (2007), Gender Equality as Smart Economics (A World Bank Group Gender Action Plan (2007-10)

M. Robinson ‘Foreword’ in D Buss & A Manji (eds) International law: Modern feminist approaches (2005); C Chinkin et al ‘Feminist approaches to international law: Reflections from another century’ in Buss & Manji 17 26 28. http://www.soawr.org/en/