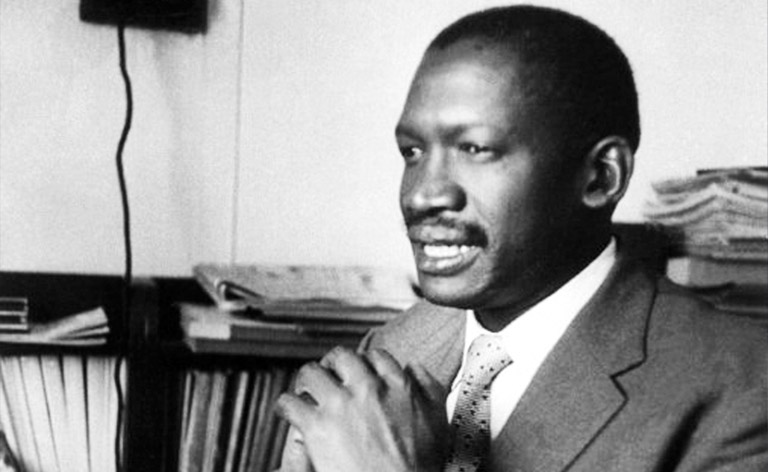

A tale of two giants: Sobukwe and Mandela

Extremely feared in life and in death, South African anti-apartheid revolutionary leader Sobukwe remains largely silenced as all attention has been lavished on Mandela. Subukwe articulated an uncompromising internationalist vision with Afrika at the centre. He eschewed multi-racialism and a narrow nationalism. Restoring land to Black people was at the heart of his praxis of liberation.

It is an odd fluke that these two men arrived and departed from this earth on the same day: Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe was born on 5 December 1924 while Mandela died on the same date three years ago. Initially counterparts in the ANC Youth League, their profound tactical differences and deep ideological and intellectual crevices were apparent right from early on. The irony of their proximity is all the more bizarre given the consistent and deliberate erasure of Sobukwe’s contribution to the Azanian and indeed global African lexicon in contrast to the effusive celebration that Nelson Mandela enjoyed in life and in death.

Sobukwe’s ideas on Africanist and African thought are canons throughout the ages and the schisms between the two men emerged as early as 1940s when the ANC Youth League was formed to respond to what South African youth believed to be the inertia of the struggle. Sobukwe, Lembede and AP Mda were among the leading lights that galvanised the Defiance Campaign and strongly opposed the policy of multi-racialism that they deemed to be a dangerous mechanism to privilege minority rights.

Sobukwe et al were extremely dissatisfied with the growing influence that the White-led Communist Party of South Africa had and by 1956 he was part of the Africanist group. Sobukwe diagnosed the South African colonial question by saying:

“The Europeans are a foreign group which has exclusive control of political, economic, social and military power. It is the dominant group. It is the exploiting group, responsible for the pernicious doctrine of white supremacy, which has resulted in the political humiliation and degradation of the indigenous African people.’

In 1959, the pressure was too much and the Africanists led by Sobukwe with AP MDA, AB Ngcobo and others left to form the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC).

Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and other leading members of the ANC Youth League remained in what Sobukwe considered to be a captured ANC. Capture clearly did not begin at Saxonwolde. In his memoirs, Mandela described the actions of the Africanist camp as immature, without a prospect of success. He also conceded that he felt intimidated by the intellectual vigour of his erstwhile friends and comrades Sobukwe and Lembede.

The men differed not only in tactics but also in allies. For Sobukwe and the PAC, the basis of any reconstituted society had to be African since Africans are indigenous to this country, are the majority and are the labour base.

The ANC preferred and stressed the importance of a multi–racial South Africa. Much of the leadership was at that time centred on urban mobilisation and concentrated on building an educated urban cadreship. The usurpation and distraction of a colonial liberation struggle into a Black/White issue was and remains one of the greatest fissures in the South African liberation narrative.

It is this that removed Afrikan liberation, decolonisation and land restitution from the centre of what Sobukwe articulated as the overriding reason to enter armed struggle through POQO. It translated the complexity of land occupation into race relations, anti-apartheid movement, more in keeping with the civil rights movement of the United States. POQO considered itself to have more in common with the Mau Mau in Kenya than freedom riders in Mississippi.

When Mr Mandela announced that he had fought White domination and would then fight Black domination, it was clear that the decades of ideological disagreement between himself and Sobukwe, by extension the ANC and the PAC, remained intact.

The outflow of the positive action campaign was of course the historical Sharpeville Uprising of 21 March 1960 about which Sobukwe said that greatest benefit was the loss of ‘fear of consequences of disobeying the colonial laws’. He heroically refused to plead for clemency from the settler colonial regime, arguing that it was illegitimate. A year later, Nelson Mandela repeated these sentiments and because officialdom continues to fear Sobukwe’s voice, even in his death, the mythology of these courageous words have been wrongly attributed to Tata Mandela.

Having been imprisoned for the Sharpeville Uprising, Sobukwe and other PAC cadres began to mobilise and politicise the hardened criminals that they did hard labour with. Indeed the Institute of Race Relations conducted a survey that indicated that the Africanist camp had ignited the national and even international imagination. Their 1963 survey indicated 57% support for the PAC, 39% for the ANC and 31% for the Liberal Party.

All this within just a year of PAC’s formation. Perhaps most potent contribution that Mangaliso Sobukwe made was in his ability to describe an internationalist vision with Afrika at the centre. Similar to Cabral he eschewed narrow nationalism and spoke against what he characterised as fashionable doctrine of ‘exceptionalism.’ He opined that South Africa was deeply embedded in the broader African continent and the global African experience and strongly maintained that isolationism - which the Pretoria colonial regime was trying to instil in the African majority – could not be part of the Africanist narrative.

‘Prof’, as he was affectionately known, spoke clearly on economic restitution and articulated the process required to achieve equitable distribution of wealth through industrial development. He recognised that rural poverty was causing immense pressure on the inevitable urban population, and in anticipation of governing, begun to co-create ideas to bring the Afrikan majority to the centre of economic vibrancy. At the centre of Sobukwe’s praxis of liberation was land.

The official story of Nelson Mandela is of a moderate nationalist who perhaps hoped for peaceful transition until this hope went up in the flames of the Sharpeville Uprising. Although he has been quoted as saying ‘I was bitter and felt ever more strongly that SA whites need another Isandlwana,’ most of these sentiments were laid aside in favour of the negotiated settlement.

Perhaps Sobukwe would have noted that the settlement has displaced more people particularly the Afrikan majority. The Government of National Unity was characterised by some critics as a deeply compromised response to a revolutionary threat posed by African workers. The GNU attempts to bind the workers’ organizations to the bourgeoisie. Naomi Klein noted that “Mandela, in his first postelection interview as president, carefully distanced himself from his previous statements favouring nationalization. ‘In our economic policies, there is not a single reference to things like nationalization, and this is not accidental: There is not a single slogan that will connect us with any Marxist ideology.’” Klein continuess, “they remained firmly in the hands of the same four white-owned mega conglomerates that also control 80% of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. In 2005, only 4% of the companies listed on the exchange were owned by Blacks.”

This stands in some contrast to Sobukwe’s ideology that rejected ‘economic exploitation of the many for the benefit of the few‘.

In remembering the two men, the irreconcilable schisms in their politics and economic policy require examination. While Mandela had the opportunity to grow and extend his influence globally, the tragedy of Sobukwe is that in life his voice was silenced and feared. The celebration of his birth gives us the ongoing possibility of at last hearing his voice loudly pronouncing on the conditions and politics of the current era with profound prescience.

Giants, indeed, never die.

* Lebohang Liepollo Pheko is Senior Research Fellow, The Trade Collective, Managing Director - Four Rivers Trading, Steering Member - South African Women in Dialogue [SAWID] and Board Member and Africa Regional Coordinator - International Network on Migration and Development. Twitter #Lipollo99

* THE VIEWS OF THE ABOVE ARTICLE ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE PAMBAZUKA NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM

* BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* Please do not take Pambazuka for granted! Become a Friend of Pambazuka and make a donation NOW to help keep Pambazuka FREE and INDEPENDENT!

* Please send comments to [email=[email protected]]editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org[/email] or comment online at Pambazuka News.