Nkrumah’s All Africa People’s Conference: The Zimbabwean factor

The author writes about the impact the All Africa People’s Conference that was organised in December 1958 in Ghana had on liberation movements in Southern Africa, especially in Zimbabwe.

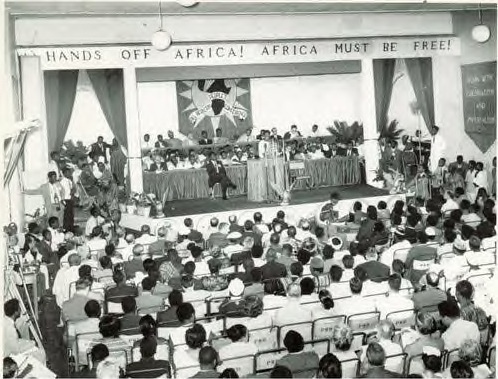

This December marks the 60th anniversary of the All African People’s Conference (AAPC) in Accra, Ghana. The nearly weeklong event in 1958 convened some 200 people representing 60 organisations from 27 countries, including prominent pan-African personalities like Patrice Lumumba and Tom Mboya. It marked a decisive shift in the organisation of pan-Africanist conferences from Europe to Africa and on the eve of the independence of many of the still colonised territories on the continent. It constitutes a key marker in the consolidation of Kwame Nkrumah’s image as a pan -African icon.

The initial impact of the AAPC was, however, much more than symbolic. An examination of the surge of political action in colonial Zimbabwe (then known as Southern Rhodesia) following the conference reveals the extent to which the AAPC contributed to deepening the liberation struggle in one of the African colonies with the strongest presence of white settlers.

Two Zimbabweans attended the AAPC conference – Joshua Nkomo, a major figure in the nationalist struggle who subsequently came to be known as “father Zimbabwe” and Paul Mushonga, who articulated a commitment to pan-African socialism but passed away early in the struggle in 1962.

Nkomo was named to the steering committee of the AAPC – attendance at its subsequent meetings across the continent enabled him to develop a range of important international contacts, which contributed to breaking the isolation the Rhodesian authorities sought to impose on the movement he led.

However, the impact of the AAPC on Zimbabwe was felt much more directly in the British colony as well.

On the side-lines of the conference, the delegates from Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi (then known as Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, respectively) which were all linked at the time in the Central African Federation, held a number of meetings and resolved that as neighbours linked under a white dominated political structure, they would increase their cooperation to push for self-determination.

Returning from Accra, H. Kamuzu Banda, leader of the liberation struggle in Malawi, transited overnight in Zimbabwe. He lodged with Mushonga and gave a blistering speech at a public meeting convened by the Zimbabwean nationalists. The speech was viewed by the settler authorities as being so incendiary, that Banda was subsequently banned from entering the colony.

In the weeks following the conclusion of the AAPC, the Southern Rhodesian government would ban several additional individuals from Malawi and Zambia from entering the colony in a bid to undermine transnational links between the liberation movements in the adjacent territories.

The meeting in Accra so unsettled the Rhodesian authorities, that on several occasions in parliament in 1959, it was discussed if legislation should be passed that would specifically ban the AAPC itself, or any political movement emanating from Ghana, from operating in Southern Rhodesia. A May 1959 government memorandum identified Ghana as the number one external threat to the security of the Central African Federation.

It was not only top government officials who were threatened by the new militancy stirred by the AAPC. Weeks after the Accra conference, a private Rhodesian citizen announced the formation of a “European National Congress” in a bid to halt the objectives of the AAPC in Southern Rhodesia.

The hysteria from the public and the increasing attention that Ghana as an agent of African liberation was receiving across the Federation spurred the government to take action. Dual states of emergency were declared in Zimbabwe and Malawi in late February and early March of 1959 and hundreds of nationalists were detained and the two main political parties in each territory were outlawed.

The fallout from this act ushered in a new stage of the liberation struggle and greatly increased support from the masses.

The impact of the AAPC was significant and extended far beyond the borders of Ghana. In convening such a diverse array of Africans, on African soil, Nkrumah struck a blow against the prevailing colonial status quo. As the anxious actions of the Rhodesian officials showed, the times were changing.

* Brooks Marmon is a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh, researching early pan-African influences on the Zimbabwean nationalist struggle.